RICK BOYLE

The walk to the Really Big Willow was Rick’s second that day. He’d passed through the clearing on his way to the Dirt Clod early that morning — and, now, as he trudged back into the Fell-Munch woods, he found himself really noticing how different everything seemed to him here at night than they had in the daytime. And how it was a really weird kind of different. And a kind he found he didn’t like. But he wasn’t afraid. He was too tired to be afraid. His head hurt too much for him to be afraid. He’d been through too much that day to worry about imagined terrors. He’d seen two dead bodies. At thinking of that, he shook his head and corrected himself: he’d seen the dead bodies of two people. Today. It didn’t feel right to call them just dead bodies, though. The word ‘bodies’ wasn’t enough. They’d been people. He’d had dealings with Victor Marsh. And he’d actually hung out with Gunny Marsh — for the first time — earlier that day. So he rephrased it in his mind that he’d seen two dead people. Which made it worse for him, but also made it more correct. Which … well, it didn’t exactly help. But, in a way, making himself feel worse in that way made it more real, and it felt right that it be real and not some prank or game. Thinking like that was how he’d missed the signs of what Mickey was going to do, he figured. He got stuck in those thoughts for a while, thinking about how the best thing and the correct thing didn’t seem to often go together there, and how he maybe hadn’t paid as much attention to what was happening as he should’ve, and what parts of what had happened were his fault, and what that meant and would mean for him. And all those swirling thoughts occupied the majority of his thoughts on the way to the Really Big Willow. But it didn’t stop him from noticing those differences in the woods. They weren’t things you could tell a story about — not to him, anyway. But he wasn’t good at telling stories like his Grandma was — which is why the weirdness of nighttime in the woods stood out to him. He noticed all that weirdness; it stuck out to him. And the more he sensed, the weirder it all seemed. It was kind of circular thinking, but Rick didn’t care. He noticed it because he wasn’t the kind of person to notice things. But whether it was because his senses were more acute after everything he’d been through, or whether it was because his Grandma was with him, or maybe something else — he noticed. He noticed the way the moonlight seemed to hit patches of water in weird ways. He noticed the way his Grandma’s flashlight had that thing where you can see the beam moving around in the dark, like in the movies. He knew that you could see it like that in fog. But it wasn’t all that foggy. There was a light pale mist at their feet, but mostly it was just dark. The flashlight beam looked funny to Rick in the mist — like there was a lot of smoke or dust in the flashlight’s beam that made it really stand out against the darkness, like the way flashlights look in the movies but almost never in real life. It struck Rick as weird – and so dos something else: the way the sounds carried through the woods as they walked. Every so often, he’d hear something that sounded like it came from behind him, and then he’d hear what seemed like an echo of that same sound from far off to the left or right – except, it took longer than echoes seem to take for the sound to happen again. Or maybe he was imagining it all, or something. That seemed like the best answer – the logical, reasonable answer — to Rick.

“Now, I know you don’t believe me,” Grandma Hilda said, reaching out her right hand to help Rick over a particularly rocky part of the trail. She was taking a different path than Rick had taken. “That’s one of the things I think is beautiful about all the spirits in the world. You know what? You don’t have to believe in them for them to be there; you don’t even have to believe in them for them to help you.”

“Thanks,” Rick said. He meant it — in a lot of different ways. Because — even with all the trauma of the day bringing her to him, he was always grateful for the fact that she was always there with him, being strong, when he needed her. And yeah — he felt like a total wuss, following her along on the trail as she walked along; she wasn’t even breathing hard. But as Rick felt the strength of his Grandma Hilda’s grip on his hand, he was also thinking about how lucky he was to have her in his life in that way. At a time when she could still do things with him. She wasn’t as old as you’d expect somebody you called Grandma to be. He wasn’t sure what year she was born, but he knew she was in her sixties. Which wasn’t that old, really. She didn’t wear glasses or dye her hair blue. She didn’t go to casinos. She went on hikes, and kept her grey hair in a long ponytail that went down below her back; so, yeah, she was cool.

“And they do help,” Hilda continued, once they’d gotten to the top of the hilly stretch of slippery white stones. “This used to be a riverbed, a long time ago. The rocks here were polished by water over a long, long time. But spirits sometimes decide to change things. And, somewhere, a cherry orchard comes to life and feeds the children of Drodden.” Grandma Hilda slowly panned the flashlight from the rocky hill’s base to its top. “And one of those children grows up and loves someone, and the spirits are happy. But, then, somebody looks at it — and looks at all that magic, and he disbelieves it. He calls all that ‘topography’ and he moves on. And misses the point of life. Or how you can get to the clearing fast, now that you don’t have to cross the water. Ah, but the topography man has a big office, and people call him ‘important.’ Did you notice how the stones massaged your feet on the way up? Even in your shoes?”

Rick didn’t respond; he just stood there, beside her, his eyes following the path of the flashlight beam as she moved it around.

Hilda lowered her head for a long moment, as if reverent about something; then, she turned back around toward where they’d walking toward and lifted her head back up and pointed the beam of the flashlight. “We’re almost there. It’s just ahead. The spirits can try to misdirect us, in the dark; they’ll point you in the wrong direction – turn you in circles, especially around a place like these woods. Where they’ve been for a long time, and go mostly undisturbed. Letting the stuff they’re made of settle on everything. It comes off of them. I know I’ve told you that before.”

Again, Rick didn’t answer. But he did think about the way the light and sound seemed strange here in the woods, at night. He tried to remember his science, to think of whatever the real explanations would have to be. He really tried. But, as with most of the times he tried to think of facts, the words and the letters got mixed-up in his brain. He confused his refraction from diffraction from reflection from diffusion. Sort of like the boy with the raccoon mask. The way the light had been wobbly all around him. Or the bushes where he’d been standing. From the heat of the fire, he’d decided. But he was wondering now if maybe it was something else — something to do with a different kind of science, of course. Not spirits. Rick knew his Grandma’s religion was as phony as the rest; someone, somewhere, was profiting off the stuff she bought to do what she called her ‘work.’ But it didn’t change the reality that she was trying to help. And even though he was tired, Rick knew he owed it to her to help her with this. To satisfy her that they’d done what they could.

After seeming to wait a little too long for Rick to respond, Grandma Hilda spoke again, and her voice was more grave than before: “That’s why we’re here. You’re covered with it, Rick. So were the policemen who brought you. So was that girl — Penny Greenlee? Do you know her?”

“No,” Rick whispered. He wasn’t sure if Hilda heard his response or not. It didn’t matter to him in that moment. Rick suddenly felt very cold; he realized he was hugging himself. His clothes weren’t really good for being in the woods at night. Grandma Hilda always had that poncho thing with the pockets she wore everywhere, so she was fine. He longed for his hoodie. But he realized Grandma Hilda hadn’t even really addressed how cold it would be for them. And he couldn’t remember where he’d left his hoodie, anyway. He wanted to say he’d left it behind at the Dirt Clod, but that didn’t seem right. It was his favorite hoodie, too. He did his best to occupy his brain with thinking about the hoodie instead of what his Grandma was saying about him being covered with spirit shit.

“She was covered with it, too,” Grandma Hilda said. “She lives near the woods; it makes sense for her, in a way. But now I think it’s something more — and that’s why we’re here, Friedrich.”

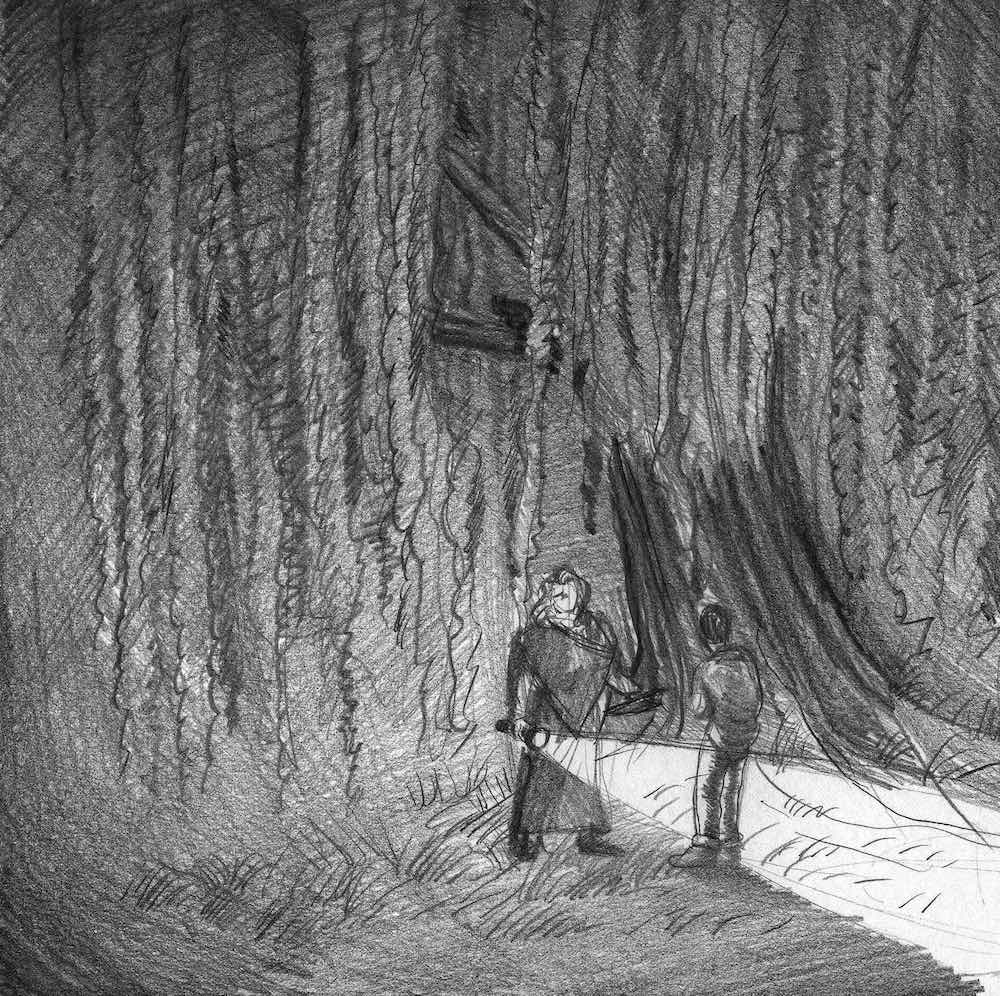

They had arrived at the clearing. In front of them was the Really Big Willow, standing tall. It looked kind of shiny, like it was made of metal, in the summer moonlight. The chilly wind blew the branches around.

Hilda walked straight over to the tree; Rick followed along. “I think your friend is in danger — all your friends. And you. And me. I think there’s a spirit out there … and I think I know what it’s doing, and what it wants. I think it wants friends. I think it’s very old, and very lonely.” She dropped the fabric bag from her right hand and twisted the top open, going to her knees to withdraw things from it: a candle, some small glass vials … and a knife.

Rick knew what Hilda’s knife — that knife — meant … to his grandmother, when she was going on about her spirits, and for Rick himself. He never liked to see it, but he’d experienced it before and he was as used to it all as he could be. He understood it was part of what she believed in, and he’d always been taught by her to respect everyone’s beliefs. He thought back to the times when that knife had come into play. He didn’t remember any of those moments hurting all that badly. But, he felt himself starting to sweat again; and, a moment later, those points of pain across his body started to sting again. And he wondered what that meant.

Grandma Hilda took the knife back into her right hand and reached up to show it to Rick. It glimmered, reflecting light from the flashlight-beam. “Did Mickey have a knife like this for the prank?”

Rick swallowed hard, and then nodded. “It was Gunny’s,” he said, walking up to stand on opposite side of the bag. “Mickey made him steal it from his dad’s place.” Rick looked to the left and right. He wasn’t sure why; he just felt the urge to make sure he couldn’t see anyone around before saying what he was about to say. Then, he blurted it: “Mickey cut Gunny’s hand with the knife!”

“That makes sense,” Hilda said, moving to stand again before taking Rick’s hands into hers. They were warm. “Taking something from Gunny’s home would’ve made the ritual much, much stronger; getting him to take it himself? Even more. It meant he was making an arrangement.”

Rick couldn’t believe he was going along with this, but it was so weird — he felt comforted by what Grandma Hilda was saying, even though it was frightening. It connected things that bothered him. It fit together. It made a weird kind of sense. More than anything, though, it let parts of his brain — that had been recoiling at all the unknowns of the last day — relax and rest. He wasn’t sure how much he believed in Grandma Hilda’s spirits, but he knew his grandmother believed in them, and he knew that affected his own life a lot. At that moment, Grandma Hilda’s belief was enough for him. At the same time, he found that he was beginning to seriously wonder if maybe Mickey believed in the same stuff Grandma Hilda did.

“I know I haven’t told you very much about my faith,” Hilda said, sounding more than a little regretful and ashamed. “Too much. I’ve kept too much from you. You’ve seen the rudiments of it. You’ve even helped. But I’ve always kept you out of so much of the meaning of it all. I know I’ve kept you locked out of it, and I’m sorry. ” She squeezed his hands. “But that’s going to change. You’re old enough to know all the things that I’ve done to protect you.” She sighed. “I’d always planned to wait until you were a little older. It wasn’t supposed to happen like this – so soon. You were supposed to be taught in other ways. You were supposed to learn by observation, over time that we don’t have now. Your grandmother has failed you, Friedrich.” She shakes her head. “But this can’t wait. I’ve got to try to give you what I can, before I leave this world. This can’t wait. There’s too much at stake. I’ve been a fool.” She managed a weak grin and shook her head. Then, “All I can promise is that I’ll do my best. I’m sorry, Friedrich. I made a mistake, but it can’t wait any more. Time for the crash-course, okay, honey?”

Rick sniffled. He squeezed his grandmother’s hands back. “Okay.” He steeled himself as best he could; he didn’t feel particularly steely, what with his stomach in knots and his head pounding now. A part of him wanted to cry. But he managed not to.

Hilda let go of his hands. “And if this is going to be a crash course, I’ll need you to always, always trust me. And listen to your grandmother now, Friedrich. If you never listen to me about anything else, listen to me now — carefully. I’m going to tell you what I tell you, and you need to do it, no matter what – without questions. No matter what your other instincts tell you, I need you to have faith.” Her voice was warmer again. “Can you do that for me, Friedrich? I need to know you can do that for me.”

“I can,” Rick said. He couldn’t think of a reason why that might be a problem. He was used to obeying Grandma Hilda. Sometimes, he wondered if that’s all he’d ever be doing for the rest of his life. He dismissed thoughts like that when he got them, most of the time. He didn’t like himself when he thought like that. She was old, and she needed him – and, when he did what she asked, and helped her, it made him feel good. It made him feel warm and happy inside.

Hilda was looking at Rick, as if appraising him up, lifting her head up and down like she was measuring him. Then she simply nodded her head. And with that, she pulled back from him, looking up at the sky. She looked back over toward Rick and approached the Really Big Willow. “So there are some rules here. I need you to pay attention to me. And most of all — once I start, don’t make a sound, no matter what you see, Friedrich. Or hear. Or feel. Okay? Be quiet. I don’t think Emmett likes loud — anything, really, when you get to it. So — I need quiet. All right — I’m starting now.” She looked back to the tree, and made to put down the flashlight. Then she lifted her left hand and tapped the flashlight gently against the side of her head, making a gesture as if berating herself for being forgetful. She looked back toward Rick with a sad look in her eyes. “The spirit’s name. You need to know it. Names have power; you know hat. This one’s name is Emmett — Emmett Beery.” Hilda set down the flashlight before lifting herself back up and holding the knife over her now-outstretched left palm. “I’ll tell you all about him, I promise; soon — but … later. Soon, I swear — but later. Yes. You’ll understand everything. Why I have to do this. Everything.” Her eyes looked far away. “Just keep yourself under control, Friedrich. And be wary; contact with a manifested spirit can cause some nausea, until you’re familiar. I’ve dealt with it before, but you haven’t. I need you to keep calm, even if that happens. It’ll pass in time. And — oh — you know I’ve told you how everyone sees most spirits differently … but he’s probably going to, well– … he’s just kind of going to look like a raccoon to you, I suppose.”

Rick’s eyes went wide. The hazy image of the boy in the raccoon mask flashed at the back of his mind. Those pinpricks of light at the back of his felt like they were stabbing him, lurching forward and driving into him just behind his eyes.

Hilda’s right hand was already lowered. The tip of the knife was just about to touch her skin.

“Grandma, wait-!” he called. He had to tell her what he’d seen.

Hilda lurched in surprise at Rick’s shout; the knife came away from her open palm. She turned toward her grandson — mouth open, lips aquiver; it was an expression of shock at having been suddenly betrayed.

And then something leapt down from the darkness of the willow branches, onto Hilda’s right arm.

Be First to Comment