EVELYN DIEDZ

Dawn returns to Drodden. The woman in purple stands by the Yellow House, the place where her case has brought her. There are secrets to the place; she doesn’t even know where to begin with it. There were wards of blood along a gravel road. There were two people, no longer living, yet both desperate to cross that road. It’s a case that’s left her with more questions than answers, so far – which isn’t unusual. She is a detective, after all, and she’s only just started to figure out the town of Drodden.

Time, however, is not on her side.

There are lives at stake. So she doesn’t want to just stand there, waiting. The detective really, really hates leaving people in danger. But she has no choice, for now. If she tried to leave on her own, she’d collapse. And, if that happened, who knows where she’d end up? Back in the Adirondacks, she suspects; maybe, even further. She’s not one of those people tethered to a particular place in the world, but she can’t risk being thrown into the maelstrom. She knows that she needs to regroup, and regain her strength, if she’s going to solve her case. She watches the sunrise, watches as the light pours through the canopied tops of the willow trees. It’s beautiful; a web of shadows falls all around her at her feet, cast by the wide, sweeping branches of the willow. She’s weaker in the sun, like most of her kind. But she can’t seek shelter in the Yellow House — not yet, anyway – and she doesn’t have the energy to go anywhere else. She knows that, eventually, in the stillness, she’ll find someone – or recover enough of her strength, even in the light, to carry on, herself. She knows she’s losing too much time, though; and, along with time, she’s also lost her name again — because, of course she has.

The detective has gotten used to losing things … people … even parts of herself. She holds her book tight to her chest. It feels cold to her, even through the fabric of her trench coat. The book is rebelling against her again, the way it always does; it happens every time, every morning after she’s gotten her name back. That’s just how it works. Mere moments ago, she’d been able to speak her name. And to write it down on the pages of the book, written in her blood. Now, though, there’s only silence when she tries to speak her name. And the letters of her name just disappear every time she tries to write them down in the book. Which she expects. But it never gets easier for her. Because, well, why should anything ever be easy for her? In spite of the fact that she knows it wouldn’t work, the woman tried one last time to force her name to appear on the pages. Once again, she fails. She tried to say her name. There’s only the sound of the natural world around her waking up. She curses. Her name is once again inaccessible to her. And it’ll stay that way until someone in the living world speaks it aloud again.

She watches as the sunrise illuminates a pale morning fog; the fog looks almost white in the morning light. She looks up at the sky again, wincing. It’s not overcast. As she waits, she looks back toward the white fog as it drifts across the ground, fighting for territory with the shadows. It worries the detective. She thinks bitterly of other times she’s seen fog like that. She tells herself not to be bitter. She tells herself that this can’t be helped, this waiting. She tells herself that it’s just how things are for her. But that doesn’t stop the increasing frustration of it all. She’s doing her best to put aside that frustration – just like always. Over the years, she’s gotten pretty good at putting aside frustration — about all kinds of things. There’s just no point in someone like her wallowing in self-pity; it’s a giant waste of time, and she knows that if she starts feeling sorry for herself it can be easy to get wrapped up in it. And, besides that, she’ll also get nowhere on her case. And, even with all that’s left to be done, she has to reminder herself that she’s come far, no matter how upset she was at how the prior day’s work turned out. She’s survived. She’s got facts she didn’t have. She’s found some people she believes are key players in the case. She’s also found the perpetrator – she thinks. Well, maybe one of them, anyway. There could be more. Which is why she’s also glad that she’s more in-tune with Drodden as a place, now. Because being more in-tune with Drodden means that — once her strength returns — she might finally be able to get around on her own — if she’s lucky. If she doesn’t make any mistakes like the many she made yesterday. But setbacks happen. And a good detective isn’t afraid of setbacks. Sometimes, in the course of running a case, bad things just happen, and you can’t stop them. And you have to deal with that. You don’t really have much of a choice. That’s just how life is, when you’re a ghost.

Which is what the woman is, of course. Hopefully, you got that from the talk about ‘the living world’ back there. But, yes, she’s a ghost, carrying around a special book as she wanders through the afterlife, probably for all eternity. And, yes, ghosts do carry things. It’s not like the movies.

Now, most living people think of chains when they think of a ghost carrying something. Or, like, the ghost’s own head. Those old, ironic curses, like in storybooks. And, yeah, it’s true that things like that happen — to the folks who get wrapped up in self-pity. That’s another reason she avoids it. The woman has seen enough self-flagellation in the world. There’s no reason to add any more to all that. Like she said, before – a waste of time.

But even she has to admit that sometimes she finds herself thinking of the book like that … like a curse. That she’s been cursed for all eternity to write in her book, using her own blood instead of ink. And, maybe, in a way, she is. Technically, do the cursed always know they’re cursed? Writing in one’s own blood sounds like a curse, in and of itself, let alone carrying the book. Except, it’s not blood in the traditional sense. That kind of blood is reserved for the living. But her teacher had told her that ghost blood worked in a similar way to human blood, and did a lot of the same things – like keeping her upright and moving forward. So it was as good a term as any.

The woman wasn’t especially great with words, anyway. She was a detective, not a writer. Not that she even felt like much of a detective at the moment. She’d come to Drodden on a case, walking most of the way. Ghosts don’t exactly have transportation systems. Well, most don’t, anyway. So how does your average detective ghost get from Point A to Point B? She walks. However long it takes. And the walk to Drodden from the Adirondacks had taken a long, long time — an exhausting time. When the detective had arrived in town, she’d been exhausted like that — because even ghosts get exhausted. It’s not uncommon, even. It’s caused by all kinds of things: sunlight, interference from random things that mess with ghosts’ physiology, having to deal with other ghosts or people trying to trap or photograph or commune with passing spirits. It’s all kinds of draining. And the woman had been drained, because she’d had to deal with all of those things on her way to Drodden. And more.

And the more drained she felt, the heavier the book felt – and the more her glowing connection to it weighed on her. Technically, she wasn’t bound to it. The connection was a tool. But she couldn’t leave it behind, for a lot of very personal reasons – even though it was broken, incomplete even still to this day. Its original creator had left it behind, unfinished. The woman and her teacher had ended up having to try and finish it themselves. The book’s original creator had been someone very important to the woman. She was someone whose face the woman knew she would never forget — could never forget, even if the woman wanted to. The book’s original creator had been someone whose voice she would always hear — someone who’d been gone a long time. When the woman had first held the book, it had still been warm from what that other person had given up to help the book first come into being. That warmth had faded a long time ago. But the book was still useful – essential — to her: everything that appeared in it became part of her own memory … after enough time had passed for her to absorb and process the maelstrom of all those surface thoughts and immediate memories; that was how she did her job; the book helped her keep track of everything, helped her locate the clues she she used to solve her cases. She couldn’t help gaining the knowledge that close contact with the living forced upon her; so, she’d long ago decided to use it for good. And the book was how she did that. But the woman knew that, even if the book did absolutely nothing, she’d still carry it with her – always — because of the life it came from, even though that life is gone now. Even though, now, all that the woman has left from back then is the book, and a business card that had the woman’s name on it. So people could maybe see it and – hopefully — read it out loud — because of the whole thing with her name. Truthfully, she didn’t know why her name got lost to her like that. Or why she had so much trouble coming through fully into the living world without people saying her name.

Her teacher had theories. He’d tried to explain a few of them to the woman, but he tended to get caught up in abstract thinking – the esoteric. The bottom line was that none of his speculations stopped it from happening, and that’s what the woman really cared about the most. Well, that … and solving the case.

“There’s blood on Fell-Munch Road. There are some woods near the road, and the blood’s there, too. Mostly animals’ blood. But not all of it.”

Those were the words she’d had to go on, at the start. A witness she’s decided is reliable. She wanted to rush in and solve it right away. She always did. But circumstances yesterday had continually kept her on the defensive. Kept her so weak that she’d been unable to do much, for most of the day. She’d managed to stumble into town, with help, but had continuously made mistakes to the point that she’d been at square one for most of yesterday.

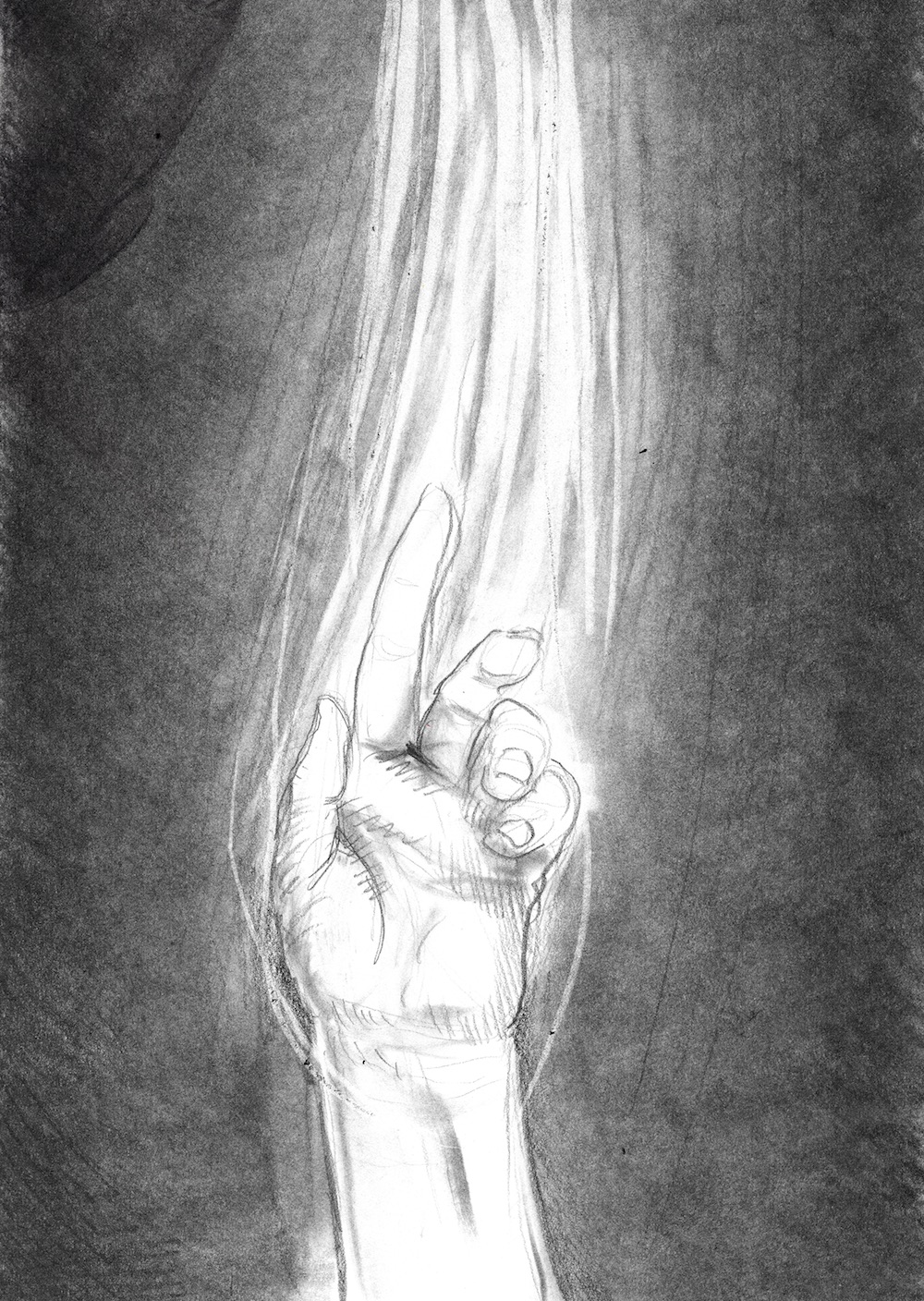

Square one being the necessity for her to use her golden cord to get around; it’s an ability all ghosts have, though not all of them figure out how to do it or have the patience to harness it properly. The golden cord allows a ghost to sort of hitch a ride with a living person. For a ghost too worn down by the stimulus of the living world, it can also be a way to rest, to recover. But it can also be a way to learn, because the cord can carry impressions, sensations … and sometimes even memories — from the living person to the ghost. But there are consequences with that. Sometimes, if the ghost is sensitive, it lets them pick up on so many impressions and memories that the ghost can become overwhelmed. Some can even forget who they are. But most simply share the experiences of the living person while they follow them with the cord. The memories, though? Well, if the ghost has a book like the detective’s, go into the book. It’s an essential tool for a detective like the woman, though she has to be careful with it — because the cord is just a tag-along, but some ghosts use it for other purposes. You see, the detective’s cord doesn’t touch the living person she’s following. It gets close, but doesn’t make contact, if the detective can help it. Sometimes it does, however briefly, but it’s an accidental thing. It takes energy and concentration to maintain the connection and keep that distance between the ghost and the living person. If a ghost using their cord slips, contact is made. That kind of contact can be dangerous. And that kind of contact is also how you sometimes end up with … a lot of big, big problems.

Like Cameron Stye.

She knows Cameron is a possessor – and that makes him an enemy. Automatically.

As for everyone else in Drodden – for the most part, the detective isn’t sure how the other people she’s met in Drodden fit together into her case, if they do at all. She suspects they do fit, but she can’t prove it. Or explain to anyone how. Not yet. And she needs to figure that out. Soon. There are some names she’s chosen to believe that she can trust, though: Emmett Beery. Penny Greenlee. CJ Sweet. She’s not entirely sure about even them, though. Nothing can be called a sure thing, when you’re dealing with the supernatural. She’s been fooled before. But she’s made the choice to trust. She knows, though, that she can’t afford to let herself be fooled the way she has in the past. Looks can be especially deceiving among the dead. And she knows that — if she’s let herself be fooled this time – even more people will die.

Yeah – ‘even more.’ Because, her failure has meant that people in Drodden have died. She keeps coming back to that reality. She literally needed to have figured out what’s going on as of yesterday. She didn’t manage it. She failed in her efforts to protect the people of Drodden. And two people died, because of her weakness. She’s tried to tell herself she’s blameless, that there was nothing she could do. But she can’t make herself believe it. All she can do is try to make each of the oddball puzzle-pieces fit together for her case. Because, if she wants to protect the people in Drodden from the man who’s spilling blood in their midst, it’s not enough to fight him head-on. You can’t do that with a possessor. Leave even a little of them behind, and they’ll be back. To handle it completely – to contain the rot in Drodden — she had to know who she can trust. She can’t protect everyone from everyone else. It’s just not possible. And trying to do that is what’s gotten her to where she is now — stuck here, outside the Yellow House.

Protecting people – you either managed it, or you didn’t.

The detective feels even less like a detective than usual, after yesterday. There were too many questions, and virtually no answers — just a lot of wasted time.

The detective consoles herself — a little — by considering that, at the very least, she can still hear the low hum of human lives inside the Yellow House. She can still feel the vibrations in the back of her head that tell her that there are people nearby her cord will be compatible with – people she might be able to follow. Each living person had a distinctive … well, she calls it a ‘song.’ Proximity makes it get stronger, but — even far away from the main town — she can ‘hear’ the buzzing of the people of Drodden. People were waking up. People were getting ready for the day. People traveling, working, living.

Her teacher had also taught the detective how to make what she could only think to describe as maps. She could make them appear to her alone – and she could track particular people’s ‘song’ and locate them. That would be useful, assuming she could get mobile again.

And this is how she eventually – after an agonizing wait – comes to realize that someone else is drawing closer to the Yellow House. She focuses in and realized that there are actually two people, close together. They come to a stop on Fell-Munch Road, and then one of the people heads back away from the place, while the other gets closer. The woman loses the trail of the departing person, who gets far enough away quickly enough that the departing song is lost in the buzz of life in Drodden. The detective surmises from the movement speeds involved that the two people arrived together, in a car, and the one who remains was dropped off to approach the Yellow House on-foot.

As always, the detective wants to be selective. She doesn’t just want to invade the private lives of others without reason. So, she always tries to pick and chose what she listens to, out of the mass of noise that makes up others’ song. But sometimes it’s a matter of necessity, to get from one place to another, for her to throw that courtesy aside, even if it’s just for a little while. When lives are at stake.

Like now. Especially given her condition, the detective’s abilities are particularly limited. And not everyone’s presence is as … audible to her as every other. It isn’t really hearing, after all. But that’s the best metaphor the detective can think of. It’s what she uses to explain it to other people.

When she gets to talk to other people, anyway.

But, even in the best of times, following someone with her golden cord is a challenge: a search for the right person, always being ready to move alongside that person no matter how much outside interference there is. Tethered when necessary, following along when not. The detective avoided tethering as much as she could. The distinction got muddy when the woman was this weak. Tethering didn’t harm the living person like full-on possession did.

And there are risks, too, even when just following along. One person’s song might be incredibly loud, while other people sing a whisper. People’s songs are as different as they are.

And now, she needs to listen, to see what she can learn about this new arrival at the Yellow House.

So the woman in purple focuses, the way she was taught. She narrows her focus, feeling the echoes of this new arrival. It’s a woman. That’s all the detective gets at first. The come the impressions, the recent memories — the scent of strawberry pie, appreciation for the morning birdsongs coming out of the woods. Then come echoes of names. Not the ones she is expecting; there are no Greenlees among the new arrivals, she quickly realizes. These are names the woman does not recognize: Rebecca Kind, Monroe Barrows and Emma Albrecht.

Yes, Emma Albrecht. Rebecca and Monroe – those are other people than the new arrival. They are surface impressions. One of the new arrivals, however, is Emma Albrecht. That name has the typical — well, luster — around it that the detective knows means it’s the new visitor’s own name, invisibly glowing there at the center of the song. Whenever the woman was looking to travel with someone, this is how it always worked at first, with these kinds of impressions at the start. There would be memories, sometimes — if someone’s mind turned out to be open enough — that the woman can hear as a silent song. Fears. Hopes.

Now, the detective knows that it can prove hard to keep track of her own energies when the songs of so many are surrounding her. Living people can be devastating toward ghosts, even without intent — like when May had passed through the detective’s manifestation, That’s another reason why she calls these feelings ‘songs’ – because you can get lost in them, in the same way a song can carry you away. It’s just that, for a ghost, it can be a lot more powerful — and a lot more dangerous. And losing yourself is always a distinct possibility, albeit a temporary one. Because everyone’s mind is different, and there are exceptions to every rule. But that loss of self, that immersion into someone else’s song, was usually brief. You simply overcame it, and moved on.

There were some people out in the living world, though – not many, but a few – who actually posed great danger to the detective when she used the cord to follow them. They were people whose songs seemed — on the surface — to be just like everyone else’s. Beneath the surface, though – there was no song, at all. People like that were impossible to detect. But if the woman sent out her golden cord and connected with people like that, it often proved disastrous. People like that would often trap the woman in a kind of hell.

And Emma Albrecht was one of those people.

Be First to Comment