JEFF ARMANDO

It was another headache day for Jeff Armando. Another blurry-vision day.. Regardless, though, Jeff was dutifully delivering the usual two bags’ worth of mail to the homes and home-businesses on the outskirts of town. His run was where residential homes and home-businesses ended and the Industrial District started. It was his duty alone to carry out. Mostly because nobody else at the Drodden post office wanted this route. But there were other reasons, too. It was a dull, time-consuming drive just to get out there; and deliveries went mostly to unattended business slots and a lot of elderly folks who needed him to bring the mail to the door, and neither of those scenarios were favorites among the other drivers. But Jeff didn’t mind. He didn’t care much one way or the other about businessmen, and he liked to help the elderly. Older customers was usually a welcome distraction for him. They were nice. They bothered to remember his name, when they could remember things. It let Jeff prioritize their lives over his own for a while. There was no time for considering your own headaches when you were around people who were grateful for another day of breathing. Jeff saw it as good for him. Humbling. And humbling was good, as the Bible said. Humility as a virtue was a comforting thought for Jeff Armando. Especially on a day like today.

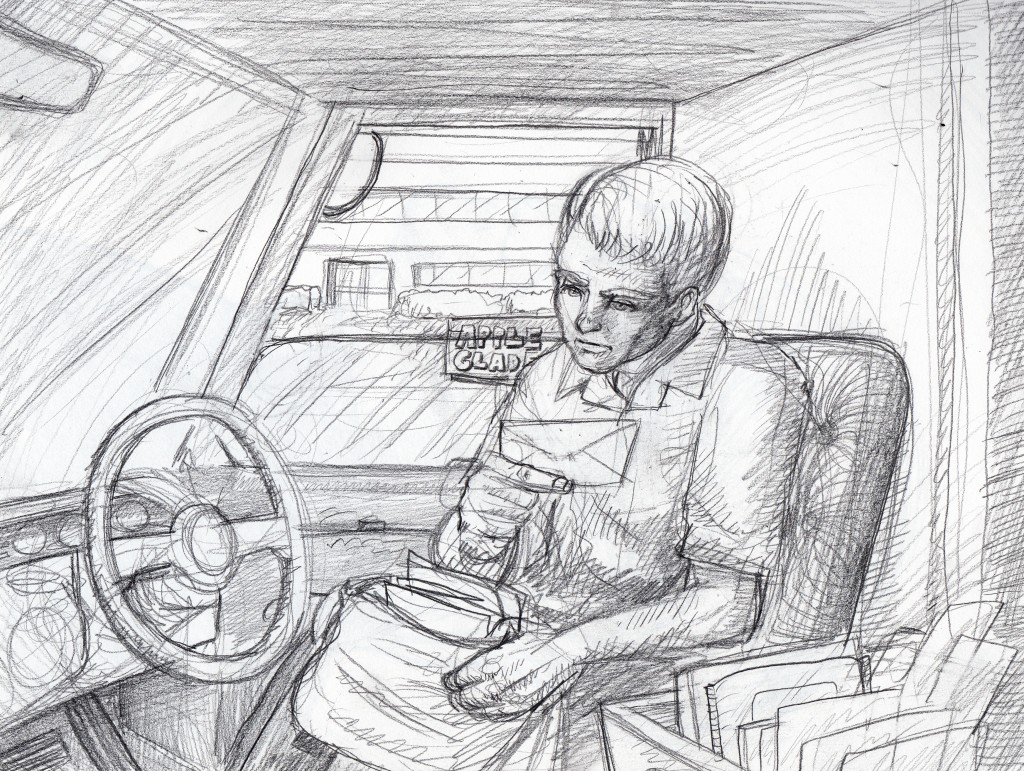

Jeff pulled up in his mail truck at the front of the Apple Glade Retirement Home. His headache was getting worse, moment-by-moment.. And Jeff Armando felt like he really didn’t want to talk to seniors, today. He wanted to just be away from almost everyone. But humility prevailed. What Jeff wanted wasn’t as important as what needed to be done. People needed their mail. There were boxes from the pharmacies. Medicine couldn’t wait on Jeff’s mood.

He realized he’d been sitting in front of Apple Glade for a while. He shook himself out of his thoughts, which also made his head hurt even worse.

Jeff retrieved the letters and packages for Apple Glade’s residents out of the appropriate mailbag.. Then, he got out of the mail truck and went through the entry doors of the Apple Glade retirement home. He walked past the glass display case at the front of the main lobby, where residents’ handcrafted figurines and other assorted knickknacks were for sale. He often bought them. He knew it helped supplement the retirees’ income. But he didn’t really want to buy any today. So, he got himself a cup of water from the cooler beside the display case, and then went over to the main desk.

As usual, there was no one there to greet him, so he decided to deliver the mail himself. He’d expected that much, of course. But he found that — even with, or perhaps because of the aches and pains plaguing him today — he felt sort of good about having followed through on this delivery. And part of that was knowing he was well-liked at Apple Glade. Jeff had always been taught to be humble, but he also had to admit to himself that he kind of enjoyed being popular with the Apple Glade residents. When he brought the retirees mail from their relatives — the few relatives who could still be bothered to write the retirees, at least — it made him feel important. And for the lonely residents who didn’t get anything from him, he even enjoyed being a conciliatory presence for them. He liked knowing someone was glad to see him.

After his deliveries there were done, Jeff walked out of Apple Glade feeling kind of reinvigorated, if still in pain. But it wasn’t anywhere near as bad as it had been when he’d left Emma’s place. The headache had started to fade; the pain had now settled from hot and piercing into something more tolerable — a dull ache behind Jeff’s eyes. The watery blurriness to his vision that he’d experienced earlier faded, too.

So, he felt renewed confidence that he’d simply been susceptible from his earlier conversation with Emma Albrecht. He got back into his truck and resumed his route, playing back his deliveries to the retirement community in his head as he drove.

About a half-hour later, Jeff turned the mail truck down onto Fell-Munch by way of Secondary Access Road. Before too long, the street’s asphalt gave way to gravel; the scenery changed to the familiar stretch of weedy flat land on one side of the road and forest on the other.

As he drove, Jeff’s thoughts kept going back toward Emma. She wasn’t much like the retirees in Apple Glade. She wasn’t really anything like them. She was always so insistent on maintaining her independence.

But he liked to help Emma, too, even though he didn’t get the accolades or, well, desperation that he got from the retirees. it was different with her; it was like how you’d help someone you don’t know that you nevertheless instinctively know is good. Like how you help someone when you know their birthday’s around the corner and you give them a discount at the local restaurant. Little things. Like helping them makes things better. Like when you know it’ll help everyone else in the community, too. And you like a person like that, almost automatically. By virtue of their connections. The way you like someone who makes pies for sick people and cares about neighbors. She was that type.

Jeff supposed most towns had someone like Emma. And even though she was twenty-five years older than him, Jeff sort of thought of her as a surrogate grandmother. He knew a lot of people who did, and he wished he could have stuck around with her for a while to make sure she got the rest she obviously needed.

Jeff came to a stop for a moment at one of the empty industrial intersections and checked his ledger again, not that he really needed to. He just felt the urge to look again, for some reason he couldn’t quite figure out.

The entirely of remaining mail on his route — a single bag — was all for the MultiMulch factory; the company was the one remaining major industrial business still operating in Drodden.

As Jeff drove past the woods near Fell-Munch, the view got empty and weedy on both sides of the road.

Jeff found himself wondering again about the big, empty buildings that dotted his horizon line on either side of Fell-Munch. As he passed them, he’d look at the broken windows and doors. He’d look at the loose trash blowing in the breeze. Plastic cups and broken bottles everywhere. The sort of junk that spoke to Jeff of adolescent parties. Jeff knew that kids would often drive out past the woods — to these old, empty buildings — to avoid the noise complaints they’d likely have back in town.

And Jeff found that he was feeling a little surge of envy. And it was upsetting. He didn’t like to feel envious of other people, for a lot of reasons. He told himself it was because he knew it was wrong, but it also served as an annoying reminder that other people had things he didn’t have. Neither of those reasons changed the reality of what he was feeling, though. And the memories were making him uncomfortable, too. Memories of hearing about parties like that back when he’d been younger, and not going to them. Either because he wasn’t invited or because he’d turned people down. And a small part of his brain objected to this kind of pining — insistent that he had no reason to be regretful, that he’d missed out on socializing by his choice to be a better student than the others. But a bigger part of him told him that he’d simply been afraid to try. With other people. That the books had been easier. The conflict in his head between the two differing versions of his history made him start to sweat. He’d read an article the weekend before on how overthinking was bad for the heart. He believed it.

So, as he drove on, he tried to distract himself by wondering how much longer it would be before the abandoned factory buildings all got demolished. They looked so similar around now, when the morning was coming. Like giant, shadowy cinderblocks. Cold, ugly and unnatural. Mayor Sharp had promised to get them all torn down, but the crisis with the hospital and police station had forced her to curtail those plans. Jeff had been on the town improvement committee. He knew the budget just wasn’t there. He also knew that the buildings would likely stay up until they fell down on their own or until some drunk kid pushed too hard on the wrong wall. And — try as he might — Jeff couldn’t force himself to feel too bad about that.

He kept trying to push away the images in his mind. Drunken kids crushed under rubble. Blood and grey concrete. Slurred screams of surprise. Someone calling for a mom who wouldn’t come. And other things. Things that he hated to think about. Things he wanted out of his head. But they wouldn’t leave the front of his brain.

He sped up the truck.

After another half-hour of driving, Jeff arrived at the end of Fell-Munch road, which turned into the parking lot of MultiMulch Inc. They made fertilizer, and other farming products. So had a lot of the other factories that Jeff had passed earlier.

Chet-Array, Beau-T-Standards, Carlaisle Lawncare.

And some others Jeff could only remember from their logos.

But, out of all of them, only MultiMulch had survived.

From the outside, the MultiMulch building was pretty much the same as those abandoned factories in terms of structure — a square grey block. The only ways you could tell for sure that MultiMulch was still in business were that the their company logo was freshly-painted on the side of the building, and the pungent chemical smells of the place, and that there were no signs of the aftermath of any party on the well-tended front lawns of the facility. There weren’t even any weeds. Instead — between the edge of the parking lot and the factory — were small rectangles of freshly-cut grass. Two shipping trucks were in the parking lot, already loading up with big bags of fertilizer and other farming chemicals. Big barrels were lined up in rows near the trucks. Nobody was attending the trucks or materials; not unusual for the hour, from Jeff’s experience.

Jeff parked the truck and carried the mail inside, past the glass front doors, into the marbled lobby. The interior of the building looked — to Jeff’s way of thinking, at least — more like a bank than a place that manufactured and distributed farmwares. The air inside tasted like a bank’s, too; recycled industrial air. Jeff listened to the loud echo of his footsteps as he carried the mailbag to the front desk.

Kelley Gwerder, the receptionist — or secretary, or whatever women who answered phones and did paperwork liked to be called — was there. Jeff liked Kelley. She was about Jeff’s age. Pretty, too, in his estimation. And she always smelled like soap and vanilla. She wore glasses with those frames that pointed out on the sides, like the smart girls in beach movies wore, and she favored bright red blouses. Red was Jeff’s favorite color, so he approved.

“Hi, Kelley,” Jeff said as he reached the desk. He didn’t know how to flirt. He’d never learned. Often, when he delivered the mail to MultiMulch, he’d imagine himself coming up with some suave remark to make about some unique package in his mailbag. But nothing had ever materialized — either in the bag, or in his mind, to make that a possibility. So he settled for a more general statement this time: “Another day, another bag of mail. How’s life?”

“Busy!” Kelley said, laying both palms flat on the desktop in front of her as if to emphasize the word. “You don’t even know. Carl’s losing his mind, Jeff. Running in and out all day, saying ‘I need a vacation.'”

They both laughed quietly at that. It was loud in the big, open room.

And then Jeff thought about how two people — one of them a child — both of whom he’d known — were dead.

And how he was now laughing with Kelley, like their deaths didn’t matter. Like they didn’t matter, either. He was just expected to continue with his … function. Jeff’s face felt very, very cold.

“Jeff? Are you okay?’ Kelley had stood up from her wheeled desk-chair, her expression confused.

“No,” Jeff said, shaking his head. “I’m not. Something’s wrong.”

Kelley reached out to take the mail bag from him. “I’ve got this, Jeff.” She set the mail down on the desk in front of her. “What’s wrong? Do you want to sit down? Do you need me to call somebody?”

“Have you watched the news yet, this morning, Kelley?” It was all Jeff could think of to say.

“No?” Kelley blinked, confused, behind her glasses. “Oh, my God — did something happen, Jeff?”

“‘Did something happen?'” Jeff repeated Kelley’s words back to her.

“I’m asking you,” Kelley said, leaning forward a little more toward Jeff.

The whole conversation felt wrong to Jeff.

More wrongness for today. Even this conversation with Kelley. The order of it. The way he’d done it. Like he should’ve been gentler in bringing it up. Or not brought it up at all. Just walked back out and gotten into his truck and driven back into town and got out of his truck and ordered a sandwich from the deli downtown and finished his day and then went home after work and thought about his imaginary basset hound while he watched Minnie Monroe until he fell asleep and then gotten up the next day and kept going until the name Marsh didn’t mean anything to him any more. He looked around at the MultiMulch lobby, with its marbled floors and glass doors and golden handles. And he thought suddenly about the work that had gone into it. People sweating to break the marble and gild the door handles. He thought about people whose whole lives revolved around going to work to do elevator maintenance and how they’d have to wear pants and there were factories producing the pants. And how people would order the materials by mail, and he’d have to deliver them. Delivering pants while people did mail order, so they could spend their lives fixing elevators while people died. He wanted to laugh, but he couldn’t. It was the kind of laugh that never came, stifled inside you by real-world catastrophe.

“Jeff?”

And the laugh churned inside of him, twisting around in his stomach, burning. He thought how all these people would go home today, and then come back tomorrow and do it all again, and again — with a little variety on what he had for his meals, or which elevators they repaired, or which pants thy wore. Or whether they checked the mailbox or decided to skip it because they were tired and really wanted to just get home. And who they — he — talked to that day. In easy conversations that didn’t involve the dead, or truth, or anything challenging.And on and on until … something.

Until what, he wasn’t sure what. Death? Death covering everything?

“Jeff?”

Death — or until it got really easy to stop thinking of the things in the world he didn’t like to think about. Until everything stopped. Until Jeff stopped. Maybe even worse than how he wanted to believe in what came after death. To go through all this — and then to end up just stopping like that. He couldn’t consider it. He couldn’t even entertain it. Thinking of the mountain of packages. Counting up the times he’d delivered things, multiplying by the days — and then multiplying the years by the days. For a moment, he wondered if this was what people meant by someone’s life flashing before their eyes. But he realized how much worse it was for him, because of what he’d made of himself; it wasn’t his life passing before his eyes, at all. It was other people’s mail. Packages and boxes and postcards and birthday cards and perfumed envelopes and flyers and coupons. And then he saw faces; dim, uncomprehending faces of people collecting utility bills from his outstretched hand, doing whatever they did to pay for the utility bills. And on and on, to … stopping? He kept telling himself he was wrong, in different ways, and catalogued the faces he’d seen — the people on his route and the people he knew. Someone who could help him. A kind face. The kindest face. And, in considering kindness, Jeff Armando knew what he had to do and who he had to see. “Oh, my God,” he said out-loud, but to himself — repeating Kelley’s words, though meaning them in a very different way.

“Jeff-!” Kelley said for a third time, looking baffled and deeply worried. “You’re kind of scaring me.” She giggled nervously.

To Jeff, it was an ugly sound Vulgar and crude. It angered him. But Jeff also gratified by what Kelley had said before, about his scaring her. Not specifically because he wanted her to be scared of him. But her being scared seemed right. Jeff felt more certain than ever of a thought that came to him late at night sometimes: that perhaps everyone should be scared. All the time. And they too often weren’t. And that had to change. He realized he hadn’t answered Kelley, so he looked back over toward her. “I’m sorry,” he said, shrugging helplessly, walking backward toward the exit. “This’ll be hard to understand, I know. You’ll get it, eventually.”

“Jeff, come sit down,” Kelley said, her voice going more sympathetic than concerned, now.”I’m all right, Kelley. I just … go put on the news in the break room or something.” For reasons not even he was clear about, he was hugging the mailbag to his chest. “Just put on the news. And pray. That’s what I’m going to do. We’ll pray.”

Kelley Gwerder stood silently, watching Jeff as he backed away from her toward the glass doors that led outside.

“That’s what we should all do. Right now. I’m going to go to the Church. Go there and talk to Father Salat.” Spoken aloud, it gave him greater certainty.

Kelley looked so worried about how Jeff was behaving, and Jeff knew he was being strange. But all he could think of doing was getting to the Church. It was the one thing that was always right to do, he figured. It’s always right go to to the church. It can fight the wrongness happening here.

Jeff walked outside. He wasn’t sure, but he thought Kelley might have said something to him as he left. But he wasn’t paying attention to Kelly Gwerder at that moment.

Once outside, Jeff got back into his truck and threw the empty mailbag into the back seat. He turned his truck around and drove far above the speed limit back into Drodden, until he reached First Step Church.

Be First to Comment