GUNNY MARSH

“Shoot, gut and there you go — five dead-assed raccoons,” Jay said, lingering on the curse word and drawing it out. He tipped his head toward Mickey. “I’m chief of assassins.” He bent down, hands on his knees, to consider the corpses.

Gunny’s guts were still recoiling, but he knew that showing much more weakness might mess up why he was doing all this in the first place. “Cool,” he managed to get out, even as his throat was retching. He clamped his lips together, hard. If he was going to puke, he’d have to just swallow it before anyone could notice. This, of course, required him to inhale through his nose. He changed it around, breathing through his mouth and resigning himself to the possibility that he might just barf all over himself.

“Okay, Jay — you showed Gunny,” Mickey said. “You’re both chief of digging-the-rest-of-the-hole, now. Rick’s helped enough. Go do that thing, Rick.” He gestured for Rick to depart; the quiet boy with the scars said nothing, giving only an expressionless shrug as any indication he’d heard what Mickey asked of him before walking around toward the other side of the Clod, out of sight.

“How much more, Mick?” Jay protested. He was clearly tired of digging.

“’til I say you’re done.”

So Jay and Gunny dug, neither of them speaking. Gunny was still feeling queasy, but he also found that breathing through his mouth was helping to keep his guts calmer. He told himself to keep digging and to focus on finishing this and getting back home to his mom’s house. He suddenly had an image in his mind of her baking raccoon-shaped gingerbread cookies. He imagined Christmas, and his dad was there, too. Everyone was drinking milk and eating gingerbread. He didn’t remember a time when that had happened in real life, but trying to think back through all of his Christmases helped him keep from thinking about the dead bodies. If the other two had noticed him being ill-at-ease with the situation, neither of them were showing it. He suspected Jay might not have figured it out, but he figured that Mickey probably had and was silently judging him. That’s how Gunny felt whenever he made eye-contact with Mickey during the digging. But it was always hard to tell what Mickey was thinking. That guy’s eyes were kind of weird sometimes. It made him kind of hard to read.

Mickey lit a fresh cigarette and watching them dig. The hole eventually got deep enough that Jay could’ve easily crouched down in it. “Okay. That’s deep enough,” Mickey finally said. “We don’t wanna make it too much work for Sheriff Marsh. He’s an old man.”

Gunny’s discomfort swelled at another mention of his father. He dared to take a few steps over toward Mickey. “What’re you gonna do?” he asked. He wanted to demand a detailed explanation of the prank. But, standing in front of Mickey, all he could really do was ask that one question. He felt particularly weak.

“Report a murder,” Mickey answered, simply — flatly, flicking away the cigarette, even though he’d smoked very little of it. He reached into an inside pocket of his jacket and pulled out a square of blank white paper that was folded up the way maps are, and began to unfold it. He looked over toward Jay. “Dump ’em.”

Jay began to kick the raccoons across the dirt, one by one. “Dead-assed raccoons, dead-assed raccoons,” Jay said, in a kind of sing-songy stage whisper. “Dah-dah-dah DAH-dah, dead-assed raccoons.” Eventually, he scooted all five bodies over the dirt and into the hole. “Dah-dah-dah DAH-dah, that’s all the raccoons.” He whisked his hands, smiling. Then, he approached Gunny again, heedless of the gore on the edges of his brown canvas plimsolls. “Let’s bury ’em,”

Gunny followed Jay back to the hole, and stared down at the dead raccoons. Their bodies had piled up together at the bottom of the hole. He wondered how you tell a girl raccoon from a boy raccoon, or how old they were. Gunny couldn’t tell any of that by looking. He wondered if raccoons had families, and if any of them were related. His stomach heaved again.

Jay spat on the ground in disgust. “C’mon!” Jay said. “Puke or dig!” he said to Gunny, and began to scoop up dirt to shovel back on top of the bodies. “We all got stuff to do after this.”

Gunny looked down at the tight grip he had on the shovel. Shoulders slumping, he started helping Jay fill the hole again. On his first three scoops, he kept his gaze on his shoes. Then, on the fourth scoop, he let himself watch as the dirt fell into the hole — onto the open eyes of the dead raccoon on top of the pile of bodies. He felt tears welling up. He tried to think of himself as Grimdark Fang again. It didn’t work. He shut his eyes tight and dug the shovel into the pile of dirt he’d made, opened his eyes every so often to center himself before shutting them again, not wanting to watch the hole fill back up with dirt. It felt like it took forever, but it was eventually filled.

“All right,” Mickey said. “Good work, you two.” Dropping down to his knees next to the filled hole, Mickey laid the unfolded paper on top of it. “Jay? Go get those rocks,” Then, he reached into his pants pocket and withdrew the knife Gunny had stolen from his father. He looked up toward Gunny. “Could you come over here and help me out with this?”

Jay nodded eagerly and took off out of Gunny’s sight, back toward the other side of the Clod.

Gunny, though, was really starting to sweat. Work — like digging — always made him sweat a little, but he’d always sweat lots more when he was scared. And hearing Mickey talk like that was oddly frightening to Gunny. It didn’t seem right for Mickey’s voice. It didn’t seem to fit. But Gunny let the shovel drop to his right and approached Mickey, keeping his gaze to the ground as he knelt next to the older boy, hanging his head.

“It’s just us for a minute, so — I gotta say … I appreciate you helping — and wanting to be part of this,” Mickey said quietly to Gunny. Then, there was a pause before Mickey added “No — look up. Look at me, man.”

Gunny looked up and made eye-contact with Mickey.

Mickey nodded his head. “Right. So. So you’re going to be one of us. For real. You’ll protect us, and we’ll protect you. But you have to show us you mean it. So you know you’ll have to give us a little bit of your blood.”

“Yeah. You told me. I’m not scared of that part. But — not a lot, right? You won’t, like, really hurt me, right?”

“Trust me. Give me your right hand, man.” As he asked, he flicked open the pocket knife in his right hand, and then held out his left toward Gunny. “And don’t look away from me. Just keep looking at me, man. Just keep looking at me. And you’ll be ok.”

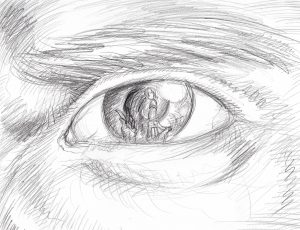

Gunny offered up his right hand to Mickey’s left one, laying his knuckles across Mickey’s palm. He kept his eyes locked onto Mickey’s, but he felt like he was seeing more than just Mickey’s eyes. He was imagining himself as one of them. Part of something. Part of something good and safe. Part of something that felt right. Gunny wanted to feel right. He wanted to be able to look at himself — really look at himself — and like what he saw. And he felt sure that this was a good first step toward that. And toward being able to look ahead instead of look back. He imagined himself with Mickey’s swagger, Jay’s confidence. He imagined himself standing with brothers and feeling like his dad would like looking at him again. And then he felt an unfamiliar sensation across the palm of his hand, like really hot and cold water running across his skin all at once. He winced, tears flooding from his eyes, but he didn’t cry out or look away from Mickey. He’d known it would hurt, but in a way it didn’t hurt as bad, because it was a kind of hurt he’d wanted.

Mickey released Gunny’s hand. “Terrific. You did it, man.” Mickey smiled his chilly smile. “Now, hold out your hand and squeeze. Over this. Up here. In the corner.” He gestured toward the top right of the paper he’d unfolded.

As Jay returned with the rocks, Gunny squeezed his bleeding hand over the blank paper. The blood poured down onto the paper, splattering like that art toy Gunny had when he was little. A little motor inside would spin a piece of paper around and you’d drop paint on it, and it would make weird patterns the way his blood was doing. Even though his hand hurt, Gunny was nevertheless fascinated with the way his blood was forming patterns on the paper. And he found himself squeezing harder, trying to make bigger patterns. He opened his hand, realizing that he wasn’t really feeling the pain in the same way he’d been feeling it a moment ago. And he tipped his head to the right and left, to get different looks at the wound running across his palm, at the flow of his blood to the paper below.

Jay started to lay the rocks down at the other edges of the paper, holding it to the ground.

Mickey was silent now, focused. He used the tip of the pocket knife to gather up the blood from the splashes in the upper right corner of the paper. He pressed the tip very lightly against the paper, drawing letters with the blood. There wasn’t really any penmanship to it, but the three could all read what Mickey had written:

HI VICK

DIG HERE

YOU KNOW ME

Be First to Comment