JEFF ARMANDO

Jeff once again didn’t bother to properly park the mail truck. He just stopped it in the midst of the First Step Church parking lot. He wasn’t allowed to drive it to personal destinations to begin with, and the church was not even close to being part of the industrial district route. He figured he was probably going to get fired. He didn’t care.

Because, in that moment, getting out of his truck and leaving its key in the ignition, Jeff kind of felt like he wanted to get fired. It seemed right. In a day where everything felt wrong.

A giddy thought came to the fore in his mind: the image of himself calling up his work and telling them where he’d left the mail truck and forcing Carter Pace — a man for whom Jeff held an intense dislike — to come and retrieve it.

But Jeff thought better of going quite that far with this. He still didn’t feel sure about what he was doing — not entirely. Not until he talked to Father Salat. He walked over the long red doormat in front of the entrance to the church.

And then — just after he took hold of the one of the golden-gilded front door-handles and pushed the doors opened onto the empty nave. — Jeff stopped

He stood very still, his hand on the cool door-handle. His tongue ached a little. He felt as if he were tasting the door-handle’s metal through his fingertips. It was a rusty taste, running all over his mouth, and it bothered him. He’d read somewhere that coppery tastes were a sign of something bad. Like your heart, or your blood, or something. He couldn’t remember. But it startled him into stopping right there for a long moment.He remembered when the folks of Drodden had — for the most part — helped in building the church.

Or, more accurately, had helped to finish building the church when the construction contract had fallen through. It had been a big community project for the congregation; volunteers lined up to do all the last-step jobs.

Like the doors.

There’d been disagreement between two men — Jeff couldn’t remember which two — on whether the doors should open outward or inward. Jeff remembered that day. It had been hot and sweaty.

Emma Albrecht had even brought out some of her ginger-brewed lemonade — which had sounded disgusting to Jeff at the time, but which he now had a taste for, himself.

But the lemonade hadn’t helped, nor the appeals for calm. Something so stupid, and it turned into a big argument.

And then Father Salat had been there. Like he always was, when people couldn’t seem to get along. He was always there when there was conflict.

And Father Salat, his glasses in his hand, wiping them with the red handkerchief he always carried concealed in his breast pocket, walked right up into the middle of the fight and looked the arguing men in the face as they both turned to face him. “Something I remember a very smart man I once met telling me: a good church draws people in; it doesn’t push people out. But did I hear Ms. Albrecht brought along some of her famous ginger lemonade?”

The argument stopped there. Everyone had felt really embarrassed. And sort of sick over how things had almost gotten violent over nothing.

Jeff felt torn. The memory reassured Jeff that he was doing the right thing by being there. But he was still having trouble taking the step that would put his foot on the inside carpet of the church.

And he still didn’t know why.

So he stood there, thinking, remembering, hand on the door-handle. He was sure he could taste the metal, and it didn’t taste good. And the more Jeff tasted it, the more the indecision gnawed at him all over his body, making his pores itch. And the fact that Jeff Armando had never been a decisive person wasn’t helping him. Just to get himself moving again, he tried out the idea of asking himself questions, hoping he’d find inspiration to come to a decision; he couldn’t even think of anything to ask himself. He couldn’t think of a thing. He wasn’t good at that sort of thing — thinking up something from nothing. He had to have a starting point. A point where something in the world gave him the start of an idea. A direction. A single direction. But, here, he was faced with two — with nothing to tell him which answer was right. It was a sickening feeling. Not like the illness of the mind that had overwhelmed him earlier, thanks to Emma Albrecht. This was more deeply-rooted, a more substantial ache in his head than any migraine. Duller, simpler — and a pain he’d known his entire lifetime. One that came when he was forced to make a decision he didn’t want to make — or to come to a conclusion he didn’t like.

Which, really, Jeff realized, was the biggest reason why he was at the church in first place. He was hoping Father Salat would help him understand a choice. Not his choice, but Mickey Laddow’s. He needed to understand. He needed answer. And, he quickly realized, he’d never get those answers just standing in the doorframe.

So — keeping himself focused on that need — he stepped inside the church.

He couldn’t see Father Salat anywhere, which made sense. It was a Wednesday. Not many people came to the church early Wednesday morning. He figured the priest was probably in the rectory.

Once through the doorway, Jeff wasn’t sure what had kept him from coming in earlier. He tried to get back to those memories, but they seemed silly and confused now. He felt the warmth of the nave, and it comforted him. The scent of incense and oil welcomed him. Some of his best memories were of First Step. He’d come here most every weekend of his childhood; his whole family had. His mother had been devout, his father, a reluctant attendee. But on Sundays, his family was together in the light that came through the big multi-colored windows. Jeff remembered watching the colors change the shade of his parents’ skin. He’d imagine the changing colors meant sins being pulled from them, yanked out of their pores by God. He remembered thinking literally of all the priests’ talk of cleansing and washing away. And he remembered thinking how his mother and father always looked brighter and shinier to him under the sunlight when his family left the church. Those moments meant a lot to him.

And Jeff Armando wanted to feel clean again.

Anointing himself with the holy water in the stoup, Jeff made the Sign of the Cross and slid into his favorite pew. The one he’d favored ever since he was little. He knelt. It felt reassuring to him, for some reason, to think of his young knees having once touched the same spot his old ones touched now. It felt like he had a sort of permanence. That was something else he needed from the church today; a reminder that things continued. Continuity itself.

He prayed for a while. He lost track of how long, but the light got brighter coming in through the windows.

Then came a familiar voice from the other end of the nave. “Hello, Jeff.”

Jeff wasn’t startled.

Somehow, Father Salat never startled Jeff.

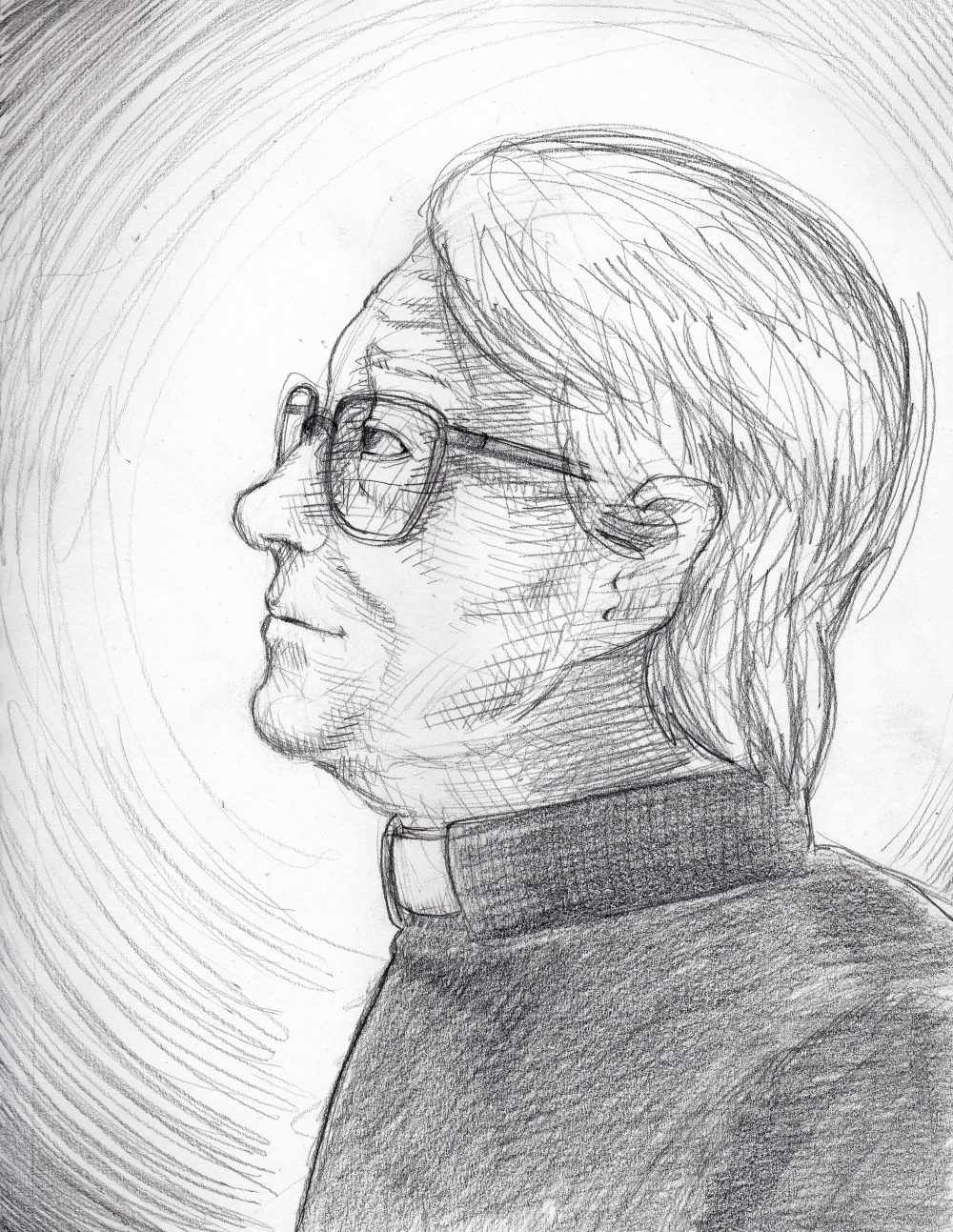

It was like the old man’s voice had a way of registering to Jeff that always calmed him, even when it came unexpectedly. Jeff looked up from where he was kneeling to see the old man approaching him, coming to a stop beside the pew. The priest was dressed in his civilian clothes, but had on his white priest’s collar anyway. Jeff couldn’t recall a time when he hadn’t seen the collar around Father Salat’s neck. Jeff then looked up from that collar a little, into the old man’s bespectacled blue eyes. “Father,” Jeff managed to say, before he felt an intense need to look away. He turned his eyes toward the image of Jesus on the Cross at the front of the church, the big statue of the Crucifixion.

Father Salat’s expression had been kind in that moment, but it seemed like there were unspoken questions changing the set of the priest’s jaw even within that brief moment.

Jeff just looked at the Crucifixion — for a long time.

Father Salat waited.

Then Jeff simply nodded, like that would answer everything.

Whatever Father Salat had planned to ask seemed satisfied by the nod. The old man sat down next to Jeff on the pew. “I was upstairs. I was resting. I must’ve heard your truck pull up. You must have woken me up, Jeff. Providence!”

Jeff stayed quiet, listening.

“Then, when I saw that it was your truck pulling up — well … ”

Jeff nodded.

“Well, Jeff, at that moment, I made a decision. I figured that, well, even though you might want some time –” and then Father Salat reached up with his right hand to gesture broadly ” — well — alone-time in here … as alone as you can get in a church when an old, foolish priest is lurking about.” Father Salat then followed Jeff’s gaze toward the statue of the Crucifixion. “But neither of us are ever really alone, here, you know?”

Tears fell down Jeff’s eyes.

Father Salat clearly saw the tears, and nodded. “I expect I know why you’re here, too, Jeff. ”

“You’ve heard about the Marshes,” Jeff said, his voice cracking, unable to look at the priest. He figured Father Salat would have had to have heard by now, from somewhere. “Am I right?”

“Yeah. You’re right,” Father Salat said. “God finds ways to tell us things. I knew that’s why you’re here — because you’re a good man, Jeff. You always seek out the light when things get darkest.” There was no doubt in the old man’s voice. “God told you to come here, didn’t He?”

“I don’t know.” Jeff never felt comfortable ascribing his own actions to God’s will. It wasn’t that he didn’t believe that there were omnipotent powers guiding everyone’s actions. He just didn’t think it was right to think of himself being the focus of God’s attention. “I don’t know,” he said again.

“But it felt right to come here, didn’t it?, Jeff?”

“Yeah,” Jeff said. He didn’t like how casual he sounded after he said that, though. Informal. Rude, somehow. Addressing a priest with “yeah.” About murders, no less. Jeff couldn’t help it. He felt too broken to do more.

“You heard that it was — that they arrested the Laddow boy … ” Father Salat said. Not a question, either. Telling Jeff something while seeming to ask. Jeff had always noticed that a lot of what Father Salat said worked like that.

“Yeah,” Jeff managed again, choking back a sob he hadn’t felt coming. That was something else Jeff knew about the priest. The old man had a way of bringing out emotions in other people. Jeff had seen him do it to far more reticent men than himself, so Jeff didn’t blame himself too much for putting on such a socially-embarrassing display. But what did trouble Jeff was that he could even be thinking about things like that in the middle of the conversation. Jeff shook off the thought. “Why would — … why would someone do something like that? I mean, why would a kid like … a child like Michael Laddow do something like that?”

Father Salat still wasn’t looking at Jeff. His eyes were fixed on the statue. The old priest exhaled a long sigh, and then shook his head. “The world has been weary and wounded for a long, long time — a lot longer than you and I’ve been around on it, Jeff,” the old priest said. “Is it any wonder our children are wounded and weary, too?”

“I was on my route — and I … ” Jeff felt shame, and hung his head.

Nobody talked for a while.

Then, Father Salat encouraged him. “Go on.”

Jeff lifted his head a little and dared to take a glance over toward the priest. The old man was staring right at the Crucifixion statue — almost, to Jeff’s way of seeing it, like he was looking right into the statue’s face. “I couldn’t do it. Not today. I … ” Jeff stopped.

“You felt like it didn’t matter. You felt futility.”

“Yes.”

“A man’s work pales next to what God’s already done. We all feel that way, Jeff. Everyone does. It’s so easy for a man to feel like he can never achieve anything important — because we can’t, except in His eyes.”

Jeff didn’t say anything.

“Even me, sometimes. I mean, remember — I spend most of time trying to talk to Him.”

But Jeff still couldn’t think of anything to say. so he just hung his head low again. His shoulders hurt, and he realized that he was tensing his muscles so hard he was really starting to shake. He cleared his throat, as if trying to encourage the priest to keep talking.

A half-minute or so of silence passed.

“I just had to get out of there.” Jeff finally said.

“There?” Father Salat asked.

“Out there.”

“The world.”

“Yeah. I just — Father, what’s the point of … you know … of a mail route, when Mike Laddow is in jail for … for maybe setting some people on fire? That’s what the news is saying. I — I mean … how can the rest of us — how can we do anything?” Jeff suddenly felt really stupid and embarrassed, looking over toward the priest, feeling a weird urge to apologize to the old man: “I’m sorry! I mean, I know I’m not making sense. I just –”

Father Salat raised his right hand again and waved it twice, dismissive of Jeff’s apology. ‘None of it,” the man said. “Jeff — I have a suggestion.”

Jeff was silent, unmoving once again, held in place — but this time in a way that felt like different to him, more like a fierce embrace than the panic of indecision.

“Stay here today. I’ll call Lucy at the Post Office. She’ll understand you need a day off. I won’t go into the details. We can sit and talk. As long as you like. And, besides, I think you might be able to help me as much as I might be able to help you. A priest is just a man, suffering as much as any other man.”

“I felt like quitting,” Jeff blurted. He wasn’t sure why, but he felt like it was important for Father Salat to know that.

“Make the decision to quit after you’re back to your old self,” Father Salat remarked, moving to stand up again. “I assure you — quitting your job will still be there as an option for you, tomorrow.” The old priest got up and motioned for Jeff to follow him. “Come upstairs to my office. I’d like you to help me with a few things, if you’ve … got the time?”

Jeff felt a strange chill go through him. It was a good chill. He’d always wondered what was upstairs in the church’s second and third floors.

“I’ll make the call,” Father Salat said, motioning again for Jeff to follow him. He began to walk toward the left corner wall of the nave, toward a wooden door that was flush with the wall. “I’m glad you came here, Jeff. You’re good to have come today,” Father Salat said as he walked away from Jeff. His voice cracked on that last word. “Don’t worry. I’ll take care of things for you.”

Jeff was finally able to get to his feet. It was like the distance from the priest reminded him he was free to move on his own. He was puzzled, momentarily, by the sensation. Then, Jeff was moving to catch up with Father Salat, who was fussing with the door. Jeff had seen Father Salat go in and out of that door many times, unlocking it with the black key from the big keyring the priest was even now lifting to the ornately-carved lock. But it wasn’t just a matter of the keys. Jeff could tell Father Salat was doing something else to get the door to open. There was more to it than just inserting a key.

Behind the door were red-carpeted stairs and painted baby-blue walls. A rose-tinted lamp with a dusty bulb hung overhead to illuminate the stairway.

“And after the call,” Father Salat continued, looking back and gesturing for Jeff to go up the stairs first, “we’ll check out the library.”

As Jeff ascended the stairs, the old priest shut the door behind them both. It locked with a click.

“I want to show you a book,” Father Salat said in a quiet voice. “It’s a book about evil. About children — and the Devil. And I think there might be answers there for the both of us, if what I’ve been hearing about what happened is true. We may not like the answers, but we need them right now. Come with me, won’t you?”

Be First to Comment