EMMETT BEERY

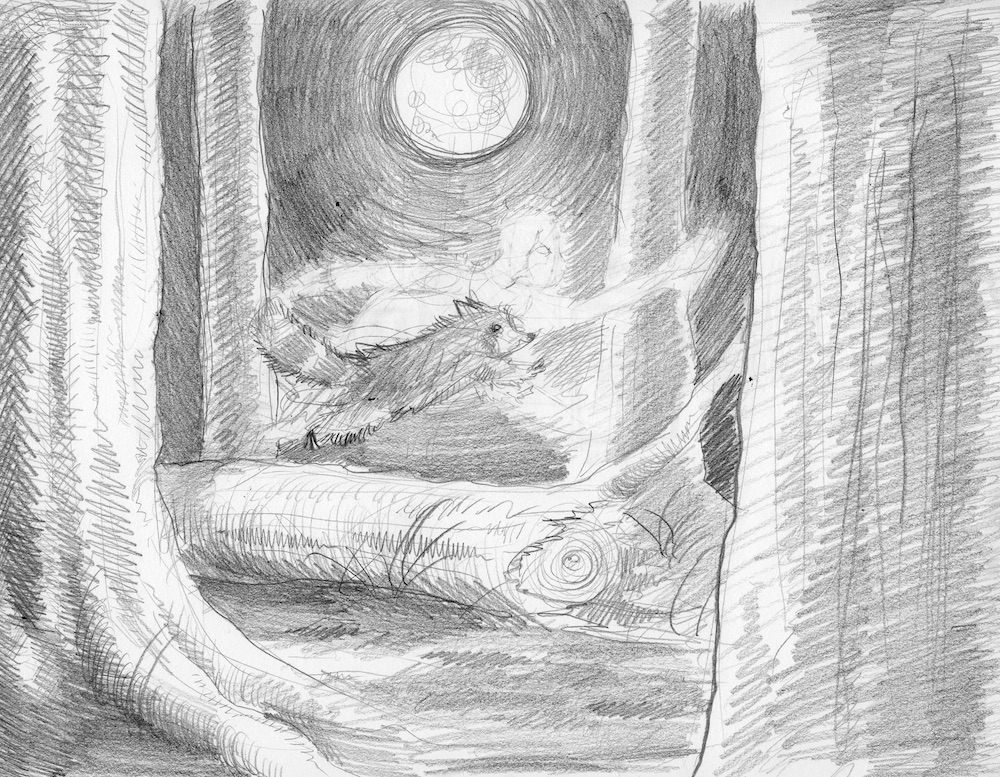

Emmett landed on all four of his feet, skittering away form both Hilda and Friedrich. He turned back to see what was happening with them.

Friedrich had veered away from focusing on Emmett; he’d just reached his grandmother’s side, as Hilda Leek was falling forward toward the ground.

Her face looked sick, like she was about to throw up, dropping to her knees in slow motion in front of her grandson.

Emmett wanted Hilda to puke all over; he thought that would be good to see.

Emmett felt angry, and confused, and it was all Hilda Leek’s fault.

He wanted to see justice happen to her.

So, as far as Emmett Beery was concerned, that woman deserved every moment of being sick that Emmett could give her.

He was really glad she’d warned Friedrich about it – because it had reminded Emmett of when he and Hilda had met up again after Emmett came back from that one time.

Emmett tried to remember if that had been the second time they’d run into each other, or the third or fourth or maybe even more – but he couldn’t remember that.

He tried to remember how long ago that had been — but he couldn’t remember that, either.

Being a ghost was messy and confusing and stupid sometimes.

Being a ghost meant that you’d be trying to do something that was happening right in front of you, and it would sometimes feel like you were doing something you’d done before.

Being a ghost meant losing track of the past and the future and the right-now.

At least, that’s how it was for Emmett.

But Emmett tried to be grateful about how things had turned out for him.

He’d still gotten away from Hilda.

He was so glad that Hilda had reminded him about how ghosts sometimes made living people sick; that had helped him get out of a bad situation, and it might have ended up helping Friedrich, too.

Ghosts were all different, and could do different things.

But what Emmett liked to do most was to help other people.

He was pretty sure that had always been important to him.

Emmett didn’t think he’d ever be able to stop trying to help people, especially now that he was a ghost.

But Emmett had forgotten that — when Hilda had first tried to catch him that one time, whichever time it had been — she’d gotten really sick from him touching her; she’d even turned colors and vomited all over the place.

That’s how he’d escaped, that one time.

He remembered the moment so clearly; it was like seeing through his eyes back to a day from the past.

But, he was also frustrated he couldn’t remember exactly when it had happened.

Emmett’s memory gave him trouble – a lot.

Like — at that moment — he was having that problem he had sometimes where he couldn’t keep track of things that were happening; it felt like the past and the present were sort of happening at the same time.

He looked down at his front feet and saw his raccoon-paws.

But he also saw the gloves his sister had given him — his super-hero gloves.

He looked back over his shoulder, and he saw the fur there.

But he also saw the hood of the fur coat that his sister had given him.

He smelled the trees and the dirt in front of him.

But, he also could smell the bad water at the bottom of a storm drain.

He could smell lemon cleaner.

He could smell snow.

And, there were voices.

All around him, there were voices.

But Emmett could tell that the voices were memories.

So, he shook his head and tried to focus.

Sometimes, things like that just happened.

Emmett figured it was just hard to explain, unless you were a ghost.

And, even though he was a ghost, he wasn’t sure even he understood it.

So, Emmett tried to block out all those distractions.

He told himself to focus on Hilda.

He told himself to focus on Friedrich.

And, most of all, he tried really hard to focus on what was happening right in front of him – specifically, Hilda being sick.

He was pretty sure he wouldn’t have remembered that past time he’d made Hilda sick, if Hilda hadn’t warned Friedrich about the nausea.

He knew something he could maybe do to fight her in the future.

It wasn’t much, but it was something.

And, Emmett also knew that it was time for him to warn Friedrich, too; he didn’t have long to do it, though.

Emmett suddenly remembered that it hadn’t taken Hilda long to recover from being sick the last time he’d grabbed her face like that.

So, as Hilda slowly dropped to her knees and started to throw up,

Emmett took action: he jumped at Friedrich, who started to jerk away from Emmett in slow motion.

He was glad Friedrich could still see him.

Having gotten Friedrich’s attention, Emmett leapt up onto the big willow tree.

Once there, Emmett reached out and slashed his right front claw-tips along the willow’s bark, concentrating really hard and thinking of what he wanted to say to Friedrich as he slashed his claws across the surface of the tree.

He was super excited when he saw the letters actually appear:

H I L D A B A D

R U N F R E E D R I K

N O W

It wasn’t much of a warning, but it was all Emmett Beery could think of and all he felt like he had time for, even with Friedrich and Hilda moving in slow motion.

Making words show up on things was a new skill he’d just figured out how to do a short while ago – but it was still hard for him, and he wasn’t good at writing or spelling anyway; he never had been.

He knew he’d somehow messed up with it when he tried to write the message for Penny, and he’d messed up again when he tried to give a message to that nice girl at the police station.

Rough things, like a rug or tree bark – he always had really hard times writing on those kinds of surfaces.

Emmett found that the trick worked better with smooth things like with the water when he’d written the message to the boy at the pond.

That had been so strange, at the pond.

The trick worked best on mirrors, though; Emmett had figured that out all by himself.

He was proud of that.

He’d made it part of the plan he’d come up with to get away from Hilda.

He’d practiced some before trying it with Penny.

So he’d been worried it wouldn’t work with Friedrich, but he’d managed to warn Hilda’s grandson about how dangerous and bad she was.

He hoped he had, anyway — hoped that Friedrich would actually be able to see the message, and understand it; Friedrich needed to realize that his grandma was a bad person.

Emmett wanted to stay and wait to make sure Friedrich could read and understand the message. But then, Emmett heard a sound up in the branches of a nearby black cherry tree.

CRACK!

It was a sound like someone snapping a big stick over their knee.

And Emmett knew what that sound meant when you heard it in these woods.

He looked up at the cherry tree, peering into the darkness, knowing that he wouldn’t catch sight of what he was sure was hiding among the flowered branches.

He never caught sight of them; only where they’d been the moment before.

CRACK!

That time, the sound had come from behind the stump of an alder – a tree exactly half as far away from him as the black cherry tree was.

Emmett ran.

He was very, very frightened.

And, he knew he had a good reason to feel that way.

Whenever he heard a crack of wood like that in the woods — like a single twig being broken in half – he knew that it meant for sure that one of Hilda’s stick-things was close.

Or, maybe more than one.

He didn’t even like to think of the stick-things, but he couldn’t help it.

Part of his being so scared of them was that Emmett had never actually seen one.

He’d used his imagination to try to come up with pictures of what they might look like – but all the pictures he came up with were pretty scary.

He would hear them make that cracking sound, and he’d sense their movements at the corners of his eyes – a shaking branch in the canopy above him, fallen leaves sent twirling into the air like something had just run through them.

They’d never caught him; he was too fast.

But that didn’t mean he wasn’t really scared of them, because he was.

He hated that cracking sound.

He didn’t want to think of what they looked like, because the cracking sound was bad enough when it came out of the woods.

Not being able to see the stick-things made them even scarier.

They were always just on the edge of things, moving around just beyond where Emmett could see, like they were trying to sneak up on him and close in on him.

Emmett remembered the stick-things chasing him; he remembered how scary they were, and how he’d always run from them.

Earlier that day, it had been the stick-things that had chased Emmett away from the tree where he’d left his message for Penny.

That had all gone so badly.

Emmett felt stupid again.

He’d been so angry about that happening, but he was too scared of what the stick-things might do to him to stick around, no matter how much he’d wanted to send Penny more messages.

He remembered writing a note to his sister on Mother’s Day because he’d written one for his mother but he hadn’t wanted his sister to be sad.

He remembered how his sister hadn’t been able to read it.

Emmett remembered explaining things to his sister, line-by-line, about what the note said.

Emmett was always really bad with writing.

When he’d written the note on the tree to Penny, earlier that morning, there hadn’t been time to explain.

There hadn’t been time — because of the stick-things.

So he’d had to run, instead of explaining what the message meant to Penny.

He always ran at any sign of the stick-things … always.

They might catch him otherwise.

And Emmett knew that would be bad.

He didn’t know how strong they were, or what they could do.

But he knew that Hilda’s weapons were dangerous.

And he knew the stick-things were Hilda’s weapons.

So, Emmett was always on the lookout for signs of the stick-things.

And there were a lot of signs that told Emmett the stick-things were watching him, a lot of the time – especially during the day … but sometimes at night, too.

As Emmett thought about that, he ran through an abandoned rabbit burrow that he knew about.

He suddenly remembered his sister had told him about different kinds of warrens and burrows and things out in the woods.

His sister had taught him about looking at nature and spotting the animals that liked to hide.

Emmett had always liked catching sight of the rabbits and skunks and badgers, back then.

But Emmett had liked the raccoons best of all.

Emmett wondered how old his sister was.

He wondered if she was still alive.

He wondered how long he’d been dead.

Sometimes, it felt to Emmett like he’d been dead for years and years.

Other times, it felt to him like all the bad things had just happened to him, like he’d just died hours ago.

It was all very confusing.

He forgot what he was doing, and stopped moving.

Then, he remembered — he was running from the stick-things.

He listened for sounds from the woods.

And then, he started running again.

He wasn’t sure how long ago he’d first realized the stick-things were on his trail.

He tried to remember how many of them there’d been.

He kept remembering other times when the stick-things had chased him.

There had been a lot of times.

So it would be easy to get them crossed.

And, Emmett had been having trouble all day with keeping track of what was happening to him right at that moment and what had happened in the past.

He felt kind of scrambled inside.

Emmett kept running, his feet getting wet from a warm puddle of muddy water as he crossed a grassy patch of open forest.

He loved his sister a lot.

He remembered his sister liked to make things.

But, so did Hilda.

Hilda had made the stick-things – actually made them out of nothing, she’d told him — just to hunt him.

He remembered how he knew that.

He remembered Hilda standing near a stream, looking younger than she did now.

He remembered her shouting at him, as he hid behind some rocks far away from her.

He remembered listening, to make sure he understood her slow-voiced cries.

She’d said she made things to hunt him.

That’s all she’d called them – things.

She’d told Emmett to run; she’d told him the whole woods would chase him forever.

And, Hilda had made that come true, because he was still running today: from Hilda, from the people she controlled, from the stick-things … and from the worst one.

The worst one made sounds out in the woods when it was near, too — like a whole bundle of twigs being snapped, all together at once.

Emmett was glad her hadn’t heard that yet that night.

Emmett didn’t even like to think about the worst one – but he was thinking about the worst one now, because Emmett was sure he was out there; he was sure the worst one looking for him, too.

The worst one was that … thing — the one that was inside of Mickey Laddow sometimes … but not always.

Emmett could tell when it was inside Mickey because Mickey would have all these glowing strings all over him, like Mickey was a puppet, like the worst one was inside of Mickey — yanking parts of him with the strings; it was so gross.

Emmett called it the worst one because it was sort of like the stick-things, but a lot worse – the worst.

Emmett had seen the worst one: it was ugly, and big, and strong, and loud.

But the glow was of the worst one was different from the glow of the stick-things.

But Emmett already knew that Hilda hadn’t made the worst one; Emmett knew that the worst one had been a person named … something Emmett couldn’t remember just then.

But the worst one had, for sure, been a person.

The worst one was a ghost, like Emmett.

Emmett just knew that was true.

But he didn’t remember how exactly he knew that.

Emmett jumped through a stream and raced along a gully, he tried to remember the worst one’s person-name.

But he couldn’t.

He just couldn’t make himself remember that.

Emmett felt like that was an important thing to remember, so he kept trying.

And, he tried to think about what he knew about the worst one — what he could remember.

He hoped maybe that would help him remember the worst one’s real name.

He hoped that maybe there’d be clues there, like what had happened with Hilda.

She’d helped him remember something, and it had helped him.

So he was trying to remember stuff about the worst one as he ran.

The worst one really had been a person once, with a person-name, but Emmett couldn’t remember it.

He knew he didn’t like to say it, whenever he did remember it.

He knew it was an ugly name – as ugly as the worst one was.

Emmett was sure that he knew the worst one’s person-name, even though he couldn’t remember it just then.

Emmett also knew that the worst one had tried to keep its person-name secret, but Emmett had figured it out.

He’d overheard the worst one and Hilda talking about the worst one’s person-name – and how the worst one went inside of Mickey Laddow.

Emmett felt really sorry for Mickey, but that didn’t change the fact that if Mickey was around … then so was the worst one.

So, Emmett knew – had known for a while — to always steer clear of Mickey Laddow.

He didn’t seem to ever forget about that.

It would have been a good trap, if Emmett hadn’t known – the worst one hiding like that, inside of Mickey, and maybe one day popping out and grabbing Emmett.

But Emmett knew better than to get caught like that.

Emmett hoped he was smarter than people gave him credit for – a lot smarter, because people were always calling him stupid.

He remembered that. But he didn’t feel smart as he ran away.

He felt like he’d failed everyone. He also knew he wasn’t smart enough to stop Hilda on his own.

He knew he needed help; he needed to find Penny, or the detective lady.

He’d been trying to remember the detective lady’s name since the police station, but he couldn’t recall that name either.

He hated how his memory kept messing up on him – especially with people’s names and with the things that had happened to him when he was alive the first time.

Those two kinds of things were usually the hardest.

Usually, it was other people who reminded him of things.

He had trouble bringing memories out on his own, but people said and did stuff that helped him remember things all the time.

The trouble was, he’d eventually forget again.

Emmett knew he was a ghost, and he was okay with that, but he hadn’t expected that being a ghost would be messy and confusing a lot of the time.

That’s not how it was in the movies.

Ghosts did stuff to people all the time in the movies.

But, for Emmett, doing stuff to make people in the real world notice was really hard.

Emmett always wondered if there was some trick to make it happen easier, the way it happened in the movies.

He imagined a ghost school, where all the ghosts were stupid and bad at things like he was.

It was funny to think about.

The thought cheered Emmett up a little.

He felt like being a ghost was kind like living inside a big mystery all the time: not much made sense, but maybe if you kept at it long enough you might be able to put some of the pieces together.

That’s what Emmett was trying to do.

But the rules kept changing, and then he had to try to figure it all out all over again.

But one thing that hadn’t changed in years was how much of his time he’d spent trying to reach out to Penny Greenlee.

Everything came back to Penny. It always did.

Emmett wanted Penny to help him so bad; but wanting her help so much made Emmett feel kind really guilty.

Emmett wanted to be a superhero, but he felt like he failed at that every time he tried.

Emmett was always trying to help the people in Drodden; he just wasn’t very good at it.

Usually, he’d just ended up getting stuck back in the willow tree; and being stuck like that made him feel like, not so much the opposite of a superhero, which was a villain, but like just a kind of person that Emmett really didn’t want to be: someone who needs to be rescued by other people.

Superheroes help other people, he knew.

They don’t ask for help; they don’t need to be rescued.

But there he was, running through the woods, hearing the sounds of the stick-thing behind him.

CRACK! CRACK! CRACK!

The sound came from three different directions, each coming a little after the other – like the cracking sounds were the stick-things communicating to each other … and there’d been three sounds.

Three stick-things were chasing him now.

So, Emmett ran faster.

He noticed that he’d reached a familiar part of the forest, where he felt like he knew the trees, and there was a path he liked to take to get away from the stick-things.

He jumped up onto a rock, and then jumped up the bark of an old alder.

Emmett remembered how his mom had taught him the names of all the different kinds of trees in the woods.

He wondered if she would think it was funny that he remembered the tree names but couldn’t remember his mom’s name.

He decided she wouldn’t like that, especially because Emmett was dead.

He remembered his mom loved him.

He wondered where his mom was. He figured she had to be alive, because otherwise she’d be with him.

He’d never been able to find his family, or even his house, ever since he’d died.

He just couldn’t remember where the people and things from that life were.

He’d spent as much time as he could – when he wasn’t running from Hilda – being on the lookout for his house.

Getting back to his house was important.

He felt like he was supposed to do something important at his house.

He remembered there had been a lot of black cherry trees near his house — on the property.

His family had owned an orchard or a farm or something – and something bad had happened there.

He wished he could remember what it was, but he couldn’t.

He felt even more stupid.

He’d tried a lot of times to find that bunch of black cherry trees.

But he just somehow never found that part of the forest – probably because of all the running-away stuff he always had to do.

It didn’t help that he couldn’t hold paper to draw a map.

When he tried to hold on to paper, his paws just went through it.

Sometimes, the paper moved when he did that, but he couldn’t hold onto it, let alone write on it with a pencil.

He’d tried to hold a pencil or pen and it had gone just like the paper – his paws would go right through the thing.

So, a map was pretty much totally impossible.

And, when you can’t make a map — and you forget a lot of stuff — it’s hard to know whether you’ve been to a place before, to rule it out when you’re looking for things like the place where you are pretty sure you might have lived at one time, back when you were alive.

But, Emmett kept on looking anyway, most days.

He knew that – even though he might not always remembered all the places he’d been — there were familiar paths in those woods that he’d visited and that he knew would help him get to other places he knew.

It was more a feeling than anything else, a familiar feeling.

But it was a good feeling, and one that Emmett liked; because, once he got on to one of those paths he usually knew at least part of where to go next.

That’s how he was feeling as he spotted a familiar clump of low-branched alder trees.

Emmett began to jump from tree-branch to tree-branch up above the forest floor.

He didn’t get tired the way he did when he was alive, especially at night, and most especially on nights with a full moon, which was out that night.

But he knew that the moonlight also probably meant that the stick-things could see him easier – if they saw things, if they had eyes.

But he didn’t want to find out whether they did or not, so he kept moving.

They tended to gang up on him, if he held still for two long.

One would chase him for a while, and then others would come, and then more. Sometimes, the trees would seem full of them, as they shook the branches and made the leaves shake.

But he’d always gotten away, every time.

They’d chase him until what seemed like forever, and then – eventually — they’d just sort of give up on their own, or he’d outrun them and they’d lose the trail.

He was never sure, but he’d still never been caught.

He didn’t want to ever be; he didn’t know what they were going to do to him, but it scared him – and just then, he was as scared as he’d ever been; and, it made him want Penny’s help even more, no matter how guilty he felt about it.

He could tell how special Penny was.

To Emmett, she was already a glowing superhero girl. He’d known it the first time he’d seen her.

He wished things could have been different, like if Emmett were alive and maybe he and Penny could’ve been friends like normal people.

He wished that every time he saw her. It made him kind of sad. He also wished that every time that he was fighting Hilda.

He didn’t like to be always running, always hiding from the hot sun that hurt him. He was all right with being a ghost, but he didn’t want to spend forever being hunted.

And he hoped Penny could help stop Hilda’s hunting.

He’d visited Penny ever since that first time he’d seen her, when he’d found the Yellow House. He knew it was called that because there was a big sign that called it that. Emmett had always had a really hard time reading, but he knew the words ‘yellow’ and ‘house.’

Emmett knew he needed to find the Yellow House again.

But he also knew that it wasn’t always that easy.

Trying to find things was hard for Emmett.

Emmett got lost a lot in the woods.

But he always loved it, when he got to the Yellow House, because there was something about that place that felt safe.

He liked the color of it.

It warmed him up inside.

Somehow, it felt like he’d be safe inside that place.

He’d felt that way since he’d first seen it.

There were a few other places with that same safe feeling – and that same color – but the other ones were far away from the woods.

The other ones were too far for Emmett to reach; he knew that he’d get snapped back to the tree, if he tried.

So he’d visited the Yellow House a lot, whenever he could find it, back when he was still doing a lot of exploring and trying to figure things out about his new life – that time before Hilda started really coming after him over and over.

Emmett liked the Yellow House and all the stuff around it; he liked sitting on that stump across Fell-Munch Road and just looking at the Yellow House.

He couldn’t remember a lot of stuff from before, but he knew he liked that place in his new life. He wondered if he’d liked it before.

He couldn’t remember, but he knew he’d liked that place for a long time.

So, he’d visited whenever he could, when he wasn’t being chased.

And then, one time, he’d seen Penny Greenlee.

Right away, he’d realized that Penny was different – because Penny just … glowed – with a great, golden light.

She did the first time Emmett had seen her, and she had when he’d seen hear those times earlier in the day.

That was how Emmett Berry had known that Penny Greenlee was a superhero girl: she glowed, even without cutting herself – and with a different kind of light than Hilda’s. Hilda’s glow always seemed so angry.

Penny’s glow just seemed calm.

And also, Penny’s glow made you want to feel calm, too.

That was a special power.

But, aside from all that, Penny had another superpower – she could see him.

He could tell that about her, because, that first time, she’d looked right out at him from inside the Yellow House; she’d looked right at him – not behind him or off to one side of him like most other people did – the people that weren’t hunting him, anyway.

Emmett had wanted to visit with Penny, but he’d never been able to get close enough – because of Fell-Much Road.

Something weird always tried to stop him whenever he started to cross Fell-Munch Road.

It always felt like something was trying to pull him down or push him back off the road.

It always felt to him like those long things that move in factories that carry stuff from one part of the factory or the other.

Emmett couldn’t remember what the factory things were called.

But that’s how it always felt; he’d try to go in one direction and end up back where he started.

He’d take a step and he’d feel like he being pushed back off the road, even though the road wasn’t moving.

The harder he tried, the harder he was pushed back.

And every time he tried, it took a little more of his energy, without him having made any progress.

It took so much of his energy that it actually hurt to try to cross.

And, if he kept at it, eventually he’d run out of energy completely … and, when that happened, he’d get carried off and wind up snapped back to somewhere else in Drodden … usually, inside the big willow tree.

Then, he’d have to stay inside the tree until he felt strong enough to leave it again.

Sometimes, that took a really long time.

He hated that, because he wasn’t sleeping when that happened.

When that happened, he’d always be awake and aware inside the tree; he just couldn’t move or do anything except think.

That was a terrible, awful feeling.

It happened so many times, that, eventually, Emmett had stopped trying to cross Fell-Munch Road … until Penny had shown up in Drodden.

That had changed things; he’d decided it was time to try to cross the road again.

He tried at least once in every year since Penny showed up in Drodden that first time, but never on the day he and Penny met each other.

His attempts were usually on the day after, when he knew it would be quieter at the Yellow House because everyone would be gone.

He imagined surprising Penny when she got back from wherever she and her family went, and he imagined she’d be so happy to see him up-close after all that time. He’d wanted to have that happen, very much.

So, he’d started trying again — usually at night, or in the early morning, when he was at his strongest. But, each time, he’d still feel that draining sensation – and that terrible loss of energy – as he got pushed back to the stump-side of Fell-Munch Road.

And, over time, he learned to accept what he shared with Penny as enough.

Yes, it made him really frustrated that all he could do was look out at her from the woods, but it’s what he knew for sure he could do; it wasn’t enough, but it was something, and you sometimes have to take something when the other choice is nothing.

That’s why he didn’t try it on the days he saw Penny looking for him out the window.

Those were special days; he didn’t want to risk losing them by trying to cross the road. If he didn’t show up one year,

Emmett had often wondered each year if she’d look the next time.

Emmett worried a lot about that.

But every year, he’d find her again.

But it wasn’t always easy.

And it wasn’t always at the Yellow House

There were exceptions – bad ones.

Like the times he’d tried to reach her on her walks in the woods, or the time with the storm drain.

With the walks, things were complicated.

Penny hadn’t always stayed inside the Yellow House during her time in Drodden.

Sometimes she’d go on walks on other days during the summer.

Emmett had followed her on a few of her walks a few times over the years, trying to do his own experiments to see if he could get her to see him in other places in the woods. But, it hadn’t worked.

Emmett guessed that maybe it was because she was always paying attention to everything in the woods and looking all over and not at one specific spot for long enough – or maybe it was just about Fell-Munch.

Emmett also wondered if maybe she had noticed, but hadn’t let on about it.

Maybe she’d noticed in an obvious way out in the woods, but she’d had to be careful because of other people Emmett hadn’t noticed.

There were a lot of clues about that, but Emmett hadn’t been smart enough yet to figure them out all the way.

Emmett had learned a long time ago that there were lots of things you had to try to figure out in your second life that you might never guess, because so much of it was so complicated and mysterious.

But, even then, Emmett had tried a few things to get her to notice him.

He’d tried writing on the tree, like he had earlier that day.

Of course, writing on the tree had turned out to be of no help at all. Penny had taken one look and run away, even though all he’d said was ‘hi ther.’ Emmett figured that Penny must have just been scared – maybe by seeing the words there on the tree when she hadn’t been expecting them.

Emmett had figured out that, when it came to Penny Greenlee, you had to be prepared for the unexpected.

Emmett’s mom – and, yes, now that he was thinking about her, he was sure he’d had a mom – had said he was ‘delicate.’

Emmett had long ago decided that Penny was delicate, too.

But she was also very strong, in different ways than superheroes are strong.

Emmett imagined Penny picking him up. He bet she could do it so easily.

She’d done it once already, without even realizing it, without even reaching for him with her hands.

That had been the time with the storm drain.

He still wasn’t sure how she’d done it. It was the time she’d carried him with her into town.

He remembered that Penny had just … done it, somehow.

He’d been on his way toward the Yellow House to see Penny that year, and he’d come out of the woods to find her standing in the middle of Fell-Munch Road, walking across it toward the tree stump, in slow motion.

Emmett had gotten so excited to see her, and she was already halfway across the road. Emmett decided, that year, to try to cross it, himself.

He ran toward her, trying to get her attention.

He didn’t think about how drained he’d feel.

He didn’t worry about anything at all except reaching Penny.

He imagined them finally meeting for real, finally being able to talk.

And it had gone awfully, terribly wrong. She hadn’t seen him.

He wasn’t sure why.

He guessed maybe because he wasn’t where he usually was.

But seeing her on the road had been too much to resist.

He’d lost all the patience and acceptance he’d usually had about what they shared.

He wanted more.

So, he’d stepped onto Fell-Munch Road, running toward Penny’s foot to try to pull at her shoe buckle to get her to look down at him.

And then, he’d felt this weird spark hit every part of his body at once – and not like the usual snap.

This had hurt much worse, and had felt much more powerful.

A moment after that, everything had gone black for him.

Since becoming a ghost, Emmett had gotten used to blackouts happening to him a lot.

That time, the next thing he’d known, though, he’d woken up in a dark place full of water. He’d tried to get a better idea of his surroundings.

He’d looked up – and he’d seen Penny Greenlee looking back at him from a grate in the ceiling of what he’d only later realize was a storm drain, once he’d had enough time to think about it.

The moment had only lasted a few seconds, but up until that moment Emmett had never experienced anything like it.

Then, the light coming down through the grate started to hurt – and then to burn — and then Emmett had found himself frozen.

Then, Emmett had felt himself snapped back – hard — into the willow.

And he’d been so exhausted by whatever had happened that he hadn’t been able to get back out of the willow again for a long, long time.

While stuck in the tree, Emmett had only really had time to think about stuff.

So, he’d done a lot of thinking about what had happened.

He’d thought about each thing that had happened to him that time and how it had happened.

And, eventually, he’d come up with the idea that Penny had somehow carried him into town that time.

Nothing else had made any sense at all.

That had to have been it.

Penny had – somehow – picked him up and carried him along into town.

That’s where Emmett had come up with his plan to get away from Hilda.

It was still the plan he was working with. And his plan was simple: get Penny to carry him with her, away from the willow tree, away from Hilda Leek, and away from Drodden, once and for all.

And then they could work together to figure out how to stop Hilda Leek – like superheroes would.

He’d worked out the whole thing: get Penny to follow him out of the house, write her a message, and get her to pick him up however she’d done it that one time.

Then, they’d go away together and be best friends and they’d leave Hilda behind and she’d just have to be angry all the time like her face was now and she’d be in jail because she was evil.

But the plan had just turned out to make a huge mess of things.

The proof of that was that Emmett was running through the woods with no idea where he was going and no idea what he was going to do next.

Emmett was pretty sure even his mom and his sister would say he’d been stupid about coming up with this plan.

It had been that bad a plan.

Emmett had scared Penny away, and then Emmett had had to run away and hide because they had all come looking for him.

Everyone – all his enemies – had come out of nowhere: Hilda, the worst one, the stick-men – all of them.

And he’d had to run and hide instead of trying to be brave alongside Penny like he’d planned.

He’d been hiding and running and trying since as long as he could remember, and he was so tired, and he felt so hopeless.

He’d counted on Penny to understand; she hadn’t.

Everything was a mistake.

Emmett really, really wanted Penny to be there in that moment.

Penny would know everything about what to do.

Emmett was certain she would help.

She already had, after all. She’d made him feel less lonely, right from the start.

She still did, even when she wasn’t around.

She made him feel less scared, too.

She seemed to care.

He wished that he’d been strong enough those other times to cross Fell-Munch Road and talk to her.

Well he wanted to talk to her in the way he talked, at least — which was to write out his words.

That hadn’t worked earlier, but he was sure he could make it work with Penny if he tried again to talk to her and thought it out more.

He couldn’t really talk, of course – not since the end of his first life.

He couldn’t even make raccoon-noises.

But he could write.

And, he knew that Penny really liked to read.

That part of the plan was still a good idea, even though Emmett had messed it up earlier that day.

That was because Emmett hadn’t been careful or smart about what he’d written.

At least, that’s what Emmett kept telling himself.

He had to believe in the plan.

He knew there were problems with his plan – lots of them – but at least he had a plan at all; it was the only plan he had to get away from Hilda and whatever bad things she was trying to do.

Emmett was angry with himself.

If he had only managed to somehow get through to Penny all those other years before, maybe things would be different.

But he hadn’t.

Penny wasn’t there to help him, no matter how much he wished.

Emmett knew wishing didn’t really help.

He knew he couldn’t just wish and have things happen.

Emmett knew that you had to make things happen.

That made him keep fighting Hilda, no matter how tired he was; no matter how cold it was outside, no matter how much it might hurt every time he tried, and no matter how many times he’d gotten snapped back to the willow.

He’d almost gotten snapped back when he’d tried that morning to get Penny’s attention with the message, when the stick things had chased him away.

Emmett had barely escaped them that time, he was pretty sure.

They’d tried to catch him by the pond, and he’d almost gotten snapped back then, too.

But they’d given up once he got to the trees near the pond.

He’d had to keep inside of the shadows of the trees so the sunlight didn’t get him.

That’s when he’d seen the Indian boy and the black girl having that picnic; he hadn’t been able to remember their names, but he’d been pretty sure he knew them, or at least had seen them before.

He’d since heard their names, but he’d forgotten them both again.

As Emmett ran across a muddy path, he tried to remember the black girl and the Indian boy’s names again; he’d seen them earlier, even before the police station.

They’d been having a picnic out by the pond with the railroad tie in the ground.

Emmett called that place Railroad Tie Pond.

He’d been frightened for them – had even tried to get their attention, despite the risk, to warn them about Hilda and the worst one and the stick-things being loose in the woods. But it hadn’t worked.

Stuff like that never worked; Emmett had tried anyway, though.

But, they’d just stared at him … and then Emmett had started to burn from the sunlight, before he’d been able to warn either of them about anything.

He’d gotten distracted and strayed too far from the shadows of the trees, and moving had gotten hard for him.

He’d run to the edge of the pond, then, and he’d been just about to jump into the water, to get away from the sunlight.

He’d gotten that feeling like he did when he was going to get snapped back to the willow.

But, just as Emmett had started to feel like he was being snapped back, he’d tried one last time to warn the Indian boy and the black girl, and – … Jay!

That was the Indian boy’s name.

Jay Redwing!

Yes, that was it. He’d suddenly remembered!

And, Emmett Beery figured that had to be something to hold on to for the moment.

But, he still couldn’t remember the name of the girl that Jay had been with; remembering Jay’s name was making Emmett feel a little bit better, though.

And then, Emmett remembered the weird way things had happened at the pond.

He remembered how Jay had looked right into his eyes, even though he’d been far away from Emmett; Emmett had looked right back into Jay’s eyes, too; somehow.

Emmett couldn’t help but do that – even though he’d been hurting so much from the sunlight burning him.

That had been right before Emmett had jumped into the water.

That had been so weird – because Emmett had felt fixed to the spot right there at the edge of the pond. It had hurt so much, being in the sunlight like that.

And Emmett suddenly remembered that Jay had been saying weird things.

That happened to people sometimes, when they were around Emmett; it was one of the reasons he was careful about approaching living people except in emergencies. Sometimes, the living people around him would get puke-y and sick, like Hilda.

Other times, though – rare times – they’d start being really weird. And they’d start saying things that — when Emmett could understand them — sounded like things Emmett might say, or maybe more like things he’d said and forgotten.

That was what it seemed most like to Emmett: things he’d said and forgotten.

Sometimes, people would just pass out, or start jumping around or yelling or flopping around on the ground out of nowhere.

He’d been confused for a while by all that, until he’d realized he’d been causing it.

So, he’d decided that staying away from people except in emergencies was the best plan.

But he hadn’t been able to help being there with Jay like that.

He’d had to warn them. And he’d ended up messing that up, too.

He’d ended up having to jump into the water, to get out of the sunlight — and then Jay had put his head in the water. It was weird.

But Emmett had been safe, for the moment; that was the thing about being underwater: it was safe in the cool darkness.

The sunlight didn’t hurt when he was underwater.

Emmett had thought for a while about living under water, since he didn’t need to breathe.

But spending time underwater always made Emmett feel sleepy, and he didn’t like to be asleep.

He felt like you missed too many things when you slept.

But Emmett hadn’t fallen asleep that time, at the pond, because of how Jay had put his face in the water.

Emmett had thought it would be a good idea to try to get a message to Jay like he had tried with Penny.

‘Tried’ was the important word there.

He’d tried to all that – but he wasn’t sure if Jay had understood, before the whole thing had gone all fuzzy and Jay got up out of the water.

Then, Emmett had started feeling really sleepy.

Normally, when he felt like that in water, Emmett would just get out of there.

But, he’d been too tired to get out on that day.

Sleep had been overcoming him.

But, just before he’d fallen asleep in the water, he’d felt a funny feeling, and he’d seen a circle of light – golden-colored light, with streaks of dark all over it.

He’d felt like he was being wrapped up by the light, and then he’d felt like he was being pulled up out of the water.

It didn’t feel like being snapped back into the willow.

The golden light with the dark colors had felt … good, not like the pain of getting snapped.

The circle of light had felt kind of like Penny’s golden light, even though the circle was a different color of gold than Penny’s light, and both were very different from Hilda’s ugly light.

So many strange things had happened to Emmett that day, that it was hard to keep track of them all, especially with his ghost-brain going this way and that.

He was really having trouble keeping track of what was happening to him right there and what had happened to him before then.

That happened a lot when he ran away from Hilda, which was a lot of the time.

Emmett would get caught up in the places he’d been and the things he’d done, and lose sight of anything but just running forward and escaping.

The way he forgot things, too, made him sometimes wonder how many times he’d had the thoughts he was having as he ran.

But one thing that stayed at the front of his mind in times like that was that he had to run.

He wasn’t a hundred-percent sure how long he’d been trying to keep away from Hilda and her monsters, but he knew he had to escape her.

So, he kept running.

He passed over some hilly ground, exposed to the moonlight, feeling the cool rays on his back.

Emmett had been surprised by how much you can feel the moonlight when you’re a ghost.

The moonlight felt really good to him, too, the way the circle of light had felt good.

Moonlight was different from sunlight; it didn’t hurt like sunlight did.

Moonlight actually made Emmett feel better when he was hurt, like that creamy stuff you’d squeeze from a tube to put on burns.

Emmett was thinking about one time when he’d burned his hand on the stove and his mom – or had it been his sister? – she’d put the cream on his hand.

He always felt safe with his sister and with his mom.

He wanted to feel safe again.

He realized then that he hadn’t heard any snapping twig sounds in a while.

He wondered if he’d outrun them. He’d been wrong about so much that day; being wrong about how close the stick-things were at that moment wasn’t a risk he was willing to take, so he tried to make himself run even faster.

He’d once come up with an idea: that when you think you’ve outrun people who are trying to hurt you, the best thing to do is to keep running for a lot longer than that, like maybe even twice as far as you’d come, just to be sure.

Emmett remembered having seen nature shows where animals thought they’d gotten away from bigger animals trying to get them.

The little animals had relaxed and then gotten caught.

Emmett knew he was a little animal compared to Hilda Leek and the monsters she used to try to get him.

But he’d evaded her all day, even though she was working so extra-hard to get him. Emmett wondered again why she was doing what she was doing.

The grass of the hill felt good on his feet.

Emmett didn’t get so tired in the moonlight; he could run forever.

But he didn’t like running away.

Emmett liked to explore; and, it’s hard to explore when you’re running away.

He thought about the new places he’d just been to that day: the pond and the police station.

He thought about how he couldn’t really even be sure that either was new to him – since he forgot so many things.

Something about the police station had been familiar, though – but he couldn’t figure out what it was.

He felt even more stupid. He felt the memory, right there — like something stuck inside of something else, where they’d been pushed together so hard they’d never get unstuck … like you’d have to push from the other end to unstick them, from inside the thing that the other thing was stuck inside of; it hurt Emmett’s head to think too much more about that, so he concentrated on running.

There’d been silence for a longer time, with no snaps of twigs for a while.

But Emmett still didn’t trust that he was safe, and he still needed to get to the Yellow House.

He realized he’d been thinking of running away on his familiar paths that he hadn’t really been going in the direction of the Yellow House.

He wasn’t sure it was the best plan, but he knew he needed to find Penny.

Thinking about it all was hard, and confusing, especially with how scared he was.

It was so easy to get lost in the woods.

Sometimes, trying to find the Yellow House, he’d end up somewhere totally different.

That’s how it had been after he’d been pulled back out of the pond. He’d looked all around, because sometimes it was hard to see in the bright sunlight, and he’d gone in the direction where it was shadiest.

That had turned out to be a place called Dog Run Trail.

That name had been familiar to Emmett, when he’d seen it on a sign.

It was a really shady trail, and he’d felt like he could rest there.

But then Friedrich had shown up. Friedrich had been able to see him, and had gotten seriously freaked out.

Emmett had been trying to write a message to Friedrich, but couldn’t make any of that work out for himself.

So he’d run again, like he was running now, like he was convinced he’d always be running.

He wasn’t sure how long he’d been running after leaving Friedrich alone, but he’d kept on running until he’d heard a very familiar voice.

“Gunny? Gunny!” the voice had called. It had been Penny’s voice.

But, here was a weird thing:

Penny’s voice hadn’t sounded slowed-down to Emmett, but Emmett had still been sure that it had been her.

Weirder still, Emmett wasn’t sure he’d ever heard Penny talk before that moment, but he somehow still knew it was her.

There was something about the voice he’d recognized.

It was Penny’s glow.

The glow was in her voice.

And, Emmett could hear it.

Emmett felt like it would be hard to explain all that, unless you were a ghost; then, you’d get it.

But the glow had been Penny’s; Emmett hadn’t had any question about that, either.

And so Emmett had run in the direction from where he’d thought he’d heard the voice.

That kind of thing was usually hard for him, but he’d felt very sure of where Penny was from those sounds.

And he’d kept hearing her voice calling out again, and again — sounding each time the way voices had sounded to him when he’d been alive.

Then, he’d heard the voice he was sure was Penny’s starting to scream:

“GUNNY! GUNNY!” Penny had stopped calling out; she’d started crying out instead; she’d been shrieking, sounding like she was in a lot of pain.

Emmett hadn’t been glad to hear Penny like that, but he’d needed it to find her again and he was glad her cries were making it easier for him to find her.

Emmett hadn’t been glad to hear Penny like that, but he’d needed it to find her again and he was glad her cries were making it easier for him to find her.

He’d come upon the trees he recognized as being the edge of the woods, before you got to Fell-Munch Road.

He hadn’t tried to come up with a plan of what he’d do; he’d just needed to see Penny, to find out why she’d been screaming, to make sure she was all right and to help her.

He’d burst out of the trees, next to the stump – and that’s when he’d seen Penny.

The sight hadn’t been good.

She’d been sitting on her knees, in the grass, on the stump side of Fell-Munch Road. She’d been yelling into her cell phone, sounding like normal-speed talking to Emmett even though she’d been moving in slow motion – which Emmett had to add to that list of mysteries. “I don’t know,” she’d said. “There’s a fire … at his house I think! He’s hurt really badly. He’s screaming. It hurts! … I can — … it HURTS!… I’M BURNING! I … oh — I — please, you’ve got to help! … It hurts! … Hello? … Hello?” Then she’d dropped the phone onto the ground and shut her eyes and then she’d started really crying; that loud sobbing that girls do sometimes that boys don’t do. She’d hugged herself, eyes closed, and she’d started rocking gently back and forth.

In that moment, everything Emmett knew about what he should do had fallen apart.

Penny had been hurting.

And, Emmett wanted to make her feel better.

Emmett had forgotten everything else.

Emmett hadn’t thought of anything else, except running toward her.

He’d forgotten in that moment about the time with the storm drain. H

e’d forgotten how hard it always was to cross Fell-Munch Road.

He wondered if he was getting any closer to Fell-Munch Road, or to the Yellow House, as he ran from the stick-things.

He wondered if he’d always approached The Yellow House from the side of the woods nearest to Fell-Munch Road.

He wondered if that meant anything.

He raced up another tree and began to leap from branch to branch.

None of those questions he was asking himself would probably have mattered to him if he had a real memory any more, he realized.

But when he’d seen Penny Greenlee cry, questions hadn’t mattered.

What had mattered to him in that moment was that Penny Greenlee had been hurting, and needed help.

So, Emmett had jumped up and down in front of her, but then he’d realized that her eyes had been closed.

That meant she wouldn’t be reading any messages he wrote.

And, he couldn’t talk — or even make raccoon-noises.

So Emmett had made a decision — probably a bad one.

As Penny had cried there in front of him, in slow motion, Emmett had instinctively leapt toward her.

There’d been no thought of the storm drain, no thought of Fell-Munch Road.

There’d been no thought of the pain.

Emmett had simply leapt toward Penny — and then, at the moment his paws should have touched her shoulder, there’d been … nothing.

There’d been a terrible sensation of nothing — for what had felt like an instant — and then came the pain.

It was like a bunch of dentist’s drills poking into him, all over his skin, all at the same time; they were twisting him and tearing at him and pulling him in all different directions.

Then, there’d been a flash of blackness.

And then, he’d woken up next in a dark hallway.

He’d felt carpeting under his feet; then, he’d remembered the time with the storm drain.

Carpeting was better than wet sewer water.

The pain had vanished as quickly as it had come.

And, you know how when you get really hurt you need time to recover?

Well, Emmett hadn’t needed that.

It was like the pain hadn’t even happened.

Emmett had felt fine as he stared down the dark hallway.

It hadn’t been like that with the storm drain.

Then, he’d been stunned by Penny carried him.

He wondered if she really had carried him, both times, without knowing it.

As he raced through a field covered with mushrooms, he wondered if that was why he could remember the time with the storm drain, because he’d done it again just a little while ago.

Thinking about both times, he felt like he should’ve known better; after all, he’d gotten snapped back to the willow just a little while after the storm drain.

But Emmett knew that, when you’re a ghost, you forget – and forgetting meant doing the same things over and over again, and sometimes maybe thinking the same thoughts; that’s just how it was, and you wouldn’t want to just sit around doing nothing just because you were worried about doing the same things or thinking the same things.

You had to try, if you cared at all — even when you were looking down a dark hallway and didn’t know where you were.

He remembered that, in the dark hallway, he’d felt disoriented from being indoors.

He’d looked up, remembering what had happened to him with the sunlight coming down into the storm drain, wondering if he’d be burned by sunlight in the police station.

But he hadn’t been burned – and there’d been no skylight.

There hadn’t even been windows.

Then, he’d remembered that – if it had been like the storm drain, then that obviously had to mean that Penny would be nearby.

He’d looked around, but he hadn’t been able to see her anywhere he looked.

The hallway had gone on in both directions for a while, with one end ending at a big round desk kind of thing.

There’d been no light at all … but Emmett’s eyes were pretty good in the dark. He looked around, trying to decide which way to go in the woods.

All the directions looked the same to him, and he wondered if it was because he was thinking more about having been in the police station than he’d been paying attention to the forest paths.

He was frustrated with himself.

There was nothing to guide him; there wasn’t even the yellow glow of the Yellow House.

There’d been a glow at the police station, though.

Emmett had noticed that strange glow in the distance in front of him, at the other end of the long hallway from the desk.

It had been a greenish glow, like the plastic rock he’d found in the woods that one time, the one that glowed in the dark.

The glow had been like that, but stronger, and shinier.

But the glow had also seemed really far away.

So Emmett had moved toward the glow, running as fast as he could toward it.

He’d raced across the carpet, gripping it tightly, digging in with his claws.

It had felt ticklish on his paws, the carpet, and it had smelled good — like someone just cleaned it.

He remembered his mom using lemon cleaner on the hardwood floors of his house.

The carpet in the hallway had smelled like that.

There hadn’t been much in the hallway to see, but on one of the walls there’d been a map, with a sign he could read – even in the dark. It had said:

DRODDEN POLICE DEPARTMENT

TEMPORARY LAYOUT

YOU ARE HERE

There’d been an arrow on the map, so Emmett had guessed that’s where he must be, too.

But he hadn’t wanted an arrow that showed where he was; he wanted an arrow that showed him where to find Penny.

He’d been certain she would be nearby, just as he’d been certain that things had happened again like the storm drain.

As he ran through the woods, jumping over a little ravine, he realized that he wasn’t sure exactly how many times Penny had carried him in the past.

Everything was becoming a jumble for him.

He remembered that his mom had used to carry him; there’d been a game where he’d pretend he couldn’t move, and she’d picked him up and he’d flop in her arms and they’d laugh.

He remembered laughing upside-down in his mom’s arms when he was little.

He remembered running across the carpet of the police station, headed toward that glow, and hoping that it would be Penny.

But it hadn’t been Penny. It had been the detective lady – the one he couldn’t remember the name of.

And she’d been with that black girl – CJ!

Her name had been – was – CJ. CJ Sweet.

He’d known her from before, too – not back when he was alive, but he’d seen her when he was a ghost.

He’d always figured she couldn’t see him.

But everything was changing.

And, there sure were a lot of people who could see Emmett lately.

There was Hilda’s grandson – but Emmett had forgotten his name.

There was Jay.

There was Penny.

And CJ?

Well …

… what had happened with her had turned out to be a big surprise to Emmett , at the police station.

He wondered if it had something to do with changes happening to him, but he realized that it probably wasn’t that – because how much did things change when you’re a ghost?

He wondered if it was the weird white mist that was on the ground of the forest.

That was new to Emmett — unless he’d forgotten about it happening before then.

He was pretty sure he hadn’t just forgotten about it.

He felt like he’d noticed it before, too, earlier that day — but he couldn’t be sure.

The mist felt cool, though – like the woods were more welcoming to him because of it.

It wasn’t something he could explain, not even to himself.

That’s just how it felt.

And he remembered he’d felt welcome by the look on the detective lady’s face when she’d looked over at him.

It had been the same kind of feeling as how the mist was making him feel.

The detective lady had looked over at him and there’d just been this feeling like when you know you can trust someone even though the feeling comes out of nowhere.

Emmett had started toward the detective lady to try to find out who she really was.

But then, the detective lady had suddenly flashed with light, like it was coming from all around her – a golden light, but different from Penny’s, with dark streaks in it … and then, she’d talked to Emmett, even though Emmett had been sure her lips hadn’t moved.

It had sounded like echoes inside his head:

“Emmett? Is that you?” she’d said. “What are you doing here? How’d you get here? I’m here to help. I’m a detective.”

But then, Emmett had seen the girl – CJ was her name – and she’d been looking right at him.

And she’d looked scared.

And then she’d started to hurt herself.

She’d been digging her fingernails into her hands, really hard.

That had gotten Emmett frightened.

He hated it when people hurt themselves.

He’d seen it bunches of times in the woods.

People hurting themselves. .. and each other.

Emmett had started to try to write a message on the carpet — but he’d been so nervous and upset by the blood coming out of CJ’s hands.

Even though CJ’s hands were closed, Emmett had still been able to see the blood.

Somehow, when you’re a ghost, you can always see blood — even when it’s hidden.

So Emmett had started to write a message on the carpet, hoping the girl would see it.

He’d tried to write a message to tell her to stop; to tell her not to hurt herself; but, even with CJ slowed down, there hadn’t been a lot of time.

She’d really started bleeding by the time he got to the second word.

Emmett didn’t let anybody hurt themselves — not while he was around.

So he’d run toward CJ instead of the detective lady — to try to pull her fingers away from where she was hurting herself.

That had gone badly, and he’d ended up getting snapped back to the willow tree.

As he raced through the woods, Emmett hoped CJ’s hands were all right.

He remembered how that had been his first thought when he’d found himself back in the willow tree.

His next thought after that had been being scared about how he hadn’t seen Penny.

And the next one after that was wondering how long he’d be stuck in the willow before he could try to find Penny again.

After all he’d been through, he remembered thinking, he’d been convinced he was going to end up stuck in that tree when Hilda came for him.

He wondered how he knew for sure that Hilda was especially trying to find him that day. He couldn’t remember.

He did remember his family being at a campfire, telling stories.

He couldn’t remember the stories, and he couldn’t see his family’s faces.

They were just blurry shapes in his memory; there was the shape of his mother and the shape of his sister – and he thought maybe there was someone else.

With the shapes being so blurry, he couldn’t really tell if he was seeing the same people as he remembered what he’d seen when they’d been around the campfire.

He just remembered a scary story he hadn’t liked.

Emmett didn’t like to be scared, and he didn’t like scaring other people, but it happened.

He wondered if Hilda was scared of him.

As he ran through a field of cattails, he thought about how he’d gotten out of the willow again, just before Hilda and Friedrich had arrived.

Emmett had felt very lucky he’d been able to come out of the tree as quickly as he had earlier, after being snapped back from the police station to the willow tree.

He hadn’t been sure how he’d gotten out of the willow so fast that particular time.

He tried to remember.

He remembered he really liked the taste of tapioca pudding.

Being pulled out of the tree had felt like having a big bowl of tapioca pudding, for some reason – good, and cold, and calming.

And, that’s when he remembered that he had been pulled out of the tree.

It wasn’t just that he’d gotten out quickly.

Something … or someone … had pulled him out of there.

He remembered being in the dark; that’s how it always happened when he was stuck inside the willow.

Usually, it took a lot of resting for him to get out.

But this day had been different.

As he’d lain there in the dark, there’d been a bright circle of golden light with dark streaks through it – and it had been like a hole he could come out of the tree through.

A realization came to him: that light had been there when he’d gotten pulled into the water with Jay.

It had been the same light.

He remembered the bright lights at his school, and how they buzzed, and how he hated them.

He liked that lights would go out sometimes when he was around.

He shook his head and tried really hard to think about the light he’d seen when he’d been pulled out of the tree. He remembered it being golden light, with streaks that were all strange and fuzzy and … there was something else that

Emmett couldn’t remember.

He felt bad about that.

He bet other people wouldn’t have any problem solving it, probably because they were better at remembering things than he was.

There were smart people in Drodden, like the detective lady.

She seemed smart.

She seemed like she’d be the kind of person who wanted to help people, like Emmett was.

And, that’s when Emmett Beery remembered that he had been pulled out of the tree. It wasn’t just that he’d gotten out quickly.

Something … or someone … had pulled him out of there.

He remembered being in the dark; that’s how it always happened when he was stuck inside the willow.

Usually, it took a lot of resting for him to get out of the tree.

But the time right after the police station had been different.

All he could do was to add the gold-and-dark light to his growing list of mysteries in his ghost-life. He had a list of things he was trying to figure out, and he just kept adding to it.

He knew wasn’t very good at finding answers to things, though. He wasn’t even sure if he’d figured things out and then forgotten them.

That’s just how it was in his new life.

He thought about what a hard day it had been.

He wondered if the hole that had pulled him somehow out of the willow had shown up because of all the weird stuff going on in Drodden that day.

He knew it probably wasn’t anything he’d done; he didn’t feel any stronger now than he did when a snap like that would keep him stuck in the tree for a lot longer time.

And, Emmett knew that if he’d been stuck in that tree, he would’ve probably been trapped, and Hilda would’ve been able to do whatever she’d wanted to do.

She’d obviously been expecting to have to force Emmett out of the tree.

She’d been expecting Emmett to hide, and she hadn’t been able to see him up in the tree branches. She hadn’t looked up into the tree.

She’d been focused on the trunk, which is where Emmett usually came out of the willow tree.

She hadn’t been paying attention. Hilda did that sometimes.

She’d spend so much time yelling and being angry that she would miss things; Emmett was glad, because a lot of times the things Hilda missed would help him get away.

He wondered if Hilda knew the detective lady was there.

He wondered if they knew each other.

And that’s when Emmett remembered something else about the detective; how she had glowed with golden light that had dark streaks in it, too.

He’d seen that glow at the pond – and at the police station – and when he’d been pulled from the willow!

He felt energized by remembering that — like a shiver was going all through him.

The detective lady had to be involved,

Emmett figured. He figured that all the times that gold and purple light had appeared just had to be connected.

He wondered if the detective lady had been helping him along the way.

He got a little excited by the thought that he might have figured out one of the mysteries on his list – but he worried he might forget it and have to puzzle it out all over again.

He really wished the writing he did didn’t just disappear after a few hours.

But it did.

He wished he could write stuff down permanently; he figured that would help him with his big problems remembering things.

But right that moment he was more concerned with running away.

He’d forgotten why he’d been running.

He remembered he was supposed to get to the Yellow House, though.

He realized that he must have been trying to get to Penny again, and then he remembered something else: Penny had been in danger the last time he’d seen her.

She’d been crying, on the ground.

She’d been crying out about being in pain — about being … on fire!

He had to get to her.

Fire was dangerous.

Fire was always dangerous.

He didn’t know what to do to get there, because he wasn’t sure where he was in the woods.

He remembered that he’d gotten lost a lot when he’d been alive.

He remembered that his big sister had always told him to think about what he’d already done so he didn’t waste time repeating himself, and to look for landmarks.

When Emmett had been alive the first time, his mom and his sister had taught him how to use landmarks: the willow tree, Fell-Munch Road, the Yellow House.

He remembered that he’d visited the Yellow House when he’d been alive the first time.

He remembered the family that had run it.

They were so nice.

The old man and woman who ran the store would round up his penny candy; like, if he had 83 cents, they’d give him a hundred pieces – every time!

He’d bought candy there, with his sister.

They’d gone on bike rides together.

He remembered walking his bike along with his sister and talking about things, as they ate their candy and looked around at the woods.

Emmett had liked doing that.

Sometimes, Emmett remembered, he’d have saved up enough to get Cowboy Cakes; he loved those. He tried really hard to think of the way from the Yellow House back to his house. But he didn’t know enough landmarks any more to figure it out; he kept trying to picture different places, and all he could remember was Hilda Leek being there.

She’d been in his path a lot that day.

At one point, she had even been very close to the worst one.

Emmett remembered something important had happened then – when Hilda and the worst one had been together.

He tried to think about it.

There hadn’t been any stick-thing sounds in a while.

The sky above was filled with moonlight, and Emmett felt like he could run faster.

He scurried down through some big tree-roots that were sticking up out of the ground.

He’d hidden from Hilda behind roots like that a lot; down inside big roots and bushes and things where he could lie really flat and she wouldn’t find him.

Emmett remembered he’d done that earlier that morning; he figured that’s why he was thinking about it.

But he’d stumbled onto Hilda and the worst one doing something.

And, Emmett had ended up right in-between them; he’d ended up right in between Hilda — with her knife — and the worst one, who was bad enough even without a knife.

But Emmett had noticed that Hilda had been carrying a big metal box, too, which had seemed weird to Emmett.

She’d never done that before.

Not even on his strongest day had she fought him by bringing that weird metal box with her.

She usually had her purse instead.

Emmett was sure that the box had been something different and new.

And, earlier today, Hilda Leek had brought that box.

Emmett had noticed that box as he’d hidden from Hilda in a bush full of bright, yellow flowers.

Emmett remembered his sister had said they were marigolds when she’d been teaching him about the woods.

She’d said marigolds were good, helpful plants.

So, Emmett had hidden there.

He’d ducked down and buried his nose into the dirt and looked at her from beneath the bush.

Hilda had just stood there, for a long time, holding out her knife, looking this way and that.

Then, she’d put the box on the ground, and then she’d taken something from around her neck and used it to open the box.

And Emmett had watched from a hiding space as she’d then taken something out of the metal box.

Emmett’s eyesight had always been bad in the light, but in his new life his eyes didn’t work even as well as they had before when it came to doing things like looking at details.

He could notice movement real easy, but reading — or getting the details of of things — well, those had both gotten really hard.

But he’d seen Hilda take something out of the box; he’d been sure of that.

Whatever she’d taken out of there, it had been about the size and shape of a small bag of laundry.

She’d dug a hole, then, in the mud.

Emmett remembered it had looked really weird, the sight of the old woman — on her knees — digging in slow motion.

Emmett had seen how occupied Hilda Leek had been with digging in the mud and had figured he could keep an eye on her and rest.

But then she’d put something in the ground, and then she’d held out the knife and made noises Emmett hadn’t understood.

Then, she’d pushed the mud back over whatever she’d put in the ground.

And Emmett had been interested.

He’d wanted to go over and dig up the hole and find whatever she’d buried.

He’d felt like it might have been something big or major or important.

But he knew he had to wait out Hilda, which had been a big part of Emmett’s big mistake at the pond earlier.

Because, after Hilda had stood back up and had left, Emmett had scurried over to the spot where the hole had been dug and tried to push the rocks off.

But he’d realized he couldn’t.

He’d made himself too weak to move even one of the rocks; he’d become too drained by traveling around hiding from Hilda, and all the other things he’d had to do.

So many things had made him tired today.

And as he’d tried to figure out what to do, he’d heard a sound from much too close-by — it had sounded like something heavy, making lots of twigs snap all at once.

He’d learned to recognize that sound, over the years, even with the funny way everything sounded to him.

Of course, the sound of napping twigs in the woods was a common one.

To Emmett, it usually sounded to Emmett these days like the big pop of his sister’s pistol.

But a whole bunch of twigs snapping like that all at once, though, always meant something a lot worse.

It meant the worst thing — the worst one. So Emmett had run away, and he hadn’t found out what had been in the metal box, or what had been buried in the ground. It had been the second time he’d had to run from that snapping sound.

The first time was when he’d tried to visit Penny in the morning.

He’d hoped this would be the year they could connect.

He had collected up every bit of his kind of light that he could manage, and he’d gone as fast as he could to the Yellow Store.

He’d known from the past that he’d get snapped back to the tree pretty quick, even with Penny around, if things didn’t go just right.

He knew that if she moved too fast or he moved too slowly or the other way around.

And he’d collected enough of his kind of light, as it had turned out, that he’d been able to lead Penny slowly to the willow tree.

And then he’d tried to use his blood to write ‘Hi there’ on the tree.

But then the twigs had scared him away, and he never got to find out if Penny really saw the message or not.

But having the worst one on his trail was less frightening than the thought of the worst one finding Penny, so he’d run as fast as he could.

So that Penny could help him get better.

So that he wouldn’t have to think about the worst one; he didn’t like to think about the man — the other one who’d been on the trail, who wasn’t Friedrich – the other man; the bad man with the horrible face he was picturing and couldn’t get out of his head.

The bad man — the one who had hurt Emmett was making Emmett think of the worst times; all that scraping, and the hands and the smell.

Emmett thought back to earlier, when he’d found Hilda and the worst one together, and how he’d hidden down in the exposed tree roots, lying flat in the mud.

He’d stayed flat like that for a long time. He remembered he’d been so scared about it all that he’d also been trying to do that trick where you don’t think of something — and failing.

He’d been trying not to think of the big drum, and being inside of it – all lined up with the other drums, all in their rows, all with their long numbers.

And how he’d felt nothing after that for the longest while.

How he’d been unable to see anything; how it had gone on for so long.

And he remembered how there’d been light and dark and then more light and then that endless-seeming dark and then the sudden, brief light that was so bright — after who knew how long — and then all that horrible burning.

That’s how it had been when he’d been born again.

He hopped over some rocks.

He was frustrated; he’d been thinking too much about the past and he worried it might get him in a lot of trouble. He got mad at himself; mix-ups happened a lot in his brain. In his new life, the past and the future sometimes got mixed-up as much as his thoughts did.

He felt like he’d already gotten mad at himself about that earlier, and he tried to remember if he’d forgiven himself.

It was hard for Emmett Beery to forgive himself about much of anything.

He didn’t like making mistakes, because superheroes don’t make mistakes – not ever.

And, he was realizing that thinking too much about being chased and the mysteries of what had happened earlier that day had managed to get him to a point where he’d become so distracted he’d stopped running.

He wasn’t sure how he’d just been standing there in the middle of the woods.

He listened as hard as he could; there were no cracking sounds from anywhere that he could hear.

But he still didn’t feel safe, and he wanted to get moving again.