JAY REDWING

Jay and CJ arrived at the front of a path that led into a large grove of black cherry trees. This was the start of the place that Jay called Risky’s Pond. If it actually belonged to anyone, neither he nor CJ knew who. Jay liked the thick black cherry trees and the way the foliage covered up the sky in the grove. Like it was more powerful than the clouds, is how Jay thought of it. It was like the clouds were always hanging over your head everywhere else, but in Risky’s Pond you got a break from that and the air was cool and smelled like a weird mix of cherries and water. Jay pulled his cell phone out of his pocket to check the time. The cell phone said 1:30 PM at first, but then it started to switch to other times: 2:27 PM, 8:27 PM. Then the screen blinked out and then came back on again. Then it turned off and then back on again. “Shit,” Jay said, stretching out the word, really emphasizing the middle of it. He looked over his shoulder toward CJ, then turned to face her. “Is your phone working? Mine is all fucking up.”

CJ reached into the front pocket of her backpack and withdrew her big, expensive-looking cell phone in its blue-and-yellow plastic case. She narrowed her gaze, pushing her glasses back up her nose and frowning at the phone. She clicked a few buttons on the side of the phone case. “Mine’s messed up, too. Weird.” She looked back over toward Jay. “It’s about, um, 1:30, I think.” She took a step closer toward Jay and made eye-contact with the boy. “We’ve got time,” she said quietly. “Let’s just get to the Pond, and we can chill by the water.”

“Cool.” Jay said, looking away from CJ and back toward his phone. “But, what the fuck, phone?” He pushed the phone back down into the left-front pocket of his denim jeans and followed the trail, with CJ right at his left. They walked slowly, Jay setting the pace. Jay was glad CJ was there, because she’d known Risky, a little bit; the three of them used to go on adventures together. Risky’s Pond had been where they’d usually stopped to have lunch back then. It was just over an hour’s walk outside of town, in the woods beyond Fell-Munch Road. Jay thought about places like Risky’s Pond, or the Dirt Clod or the Really Big Willow and all the other landmarks only the brave kids like him would go to. And, sure, Jay knew the stories about the woods. And — with Risky’s Pond being a part of those woods, and with Risky buried here — he saw all this as a place for him. All the other kids’ stories about Fell-Munch were pretty gay. Kids made up stories and stuff — but you knew that none of it was really real. It wasn’t like there were kids disappearing and stuff. His folks said some stuff happened there in real-life a long time ago, like before he’d been born — but the Jay and CJ went out there all the time and the two of them didn’t see much weird stuff. Not counting some of the shit that Mickey and Rick did for fun, anyway. Jay had come to the conclusion a long time ago that bored white kids looking for trouble in Drodden were always willing to do the weirdest shit. And, like, unprovoked, too. To people that didn’t deserve it. Rick, he knew, did a ton of weird shit because of his grandmother, who had a weird religion, going by what Jay’s parents said. But Mickey did it for laughs. But nothing worth talking about. It wasn’t like there were any chupacabra bones or piles of Sasquatch shit lying around out in the Fell-Munch woods or anything. It was a boring shit-hole full of trees, like he’d told that one lady Nothing to see; nothing worth telling that nosy black lady with the funny purple hat and coat. She’d walked right up to him and started asking him questions. Holding that hardcover book. Jay tried to remember exactly what he’d said to her, but he realized that he couldn’t. In fact, he couldn’t remember much else about the woman just now, even though he was trying really hard; he could sort of see her face and her long, curly hair. That much was floating around in his shitty, damaged brain. But the woman’s face was seriously blurry-like. And he couldn’t even remember her name. He’d seen her around town that morning. She’d said she’d been asking people what they stories they’d heard about the Industrial District, and the woods, and Fell-Munch. Jay had figured that maybe she’d been, like, a reporter or something doing a story for somebody — like what people on the street thought. ‘For human interest,’ she’d maybe said? She’d said something about how it was ‘for human interest.’ But whatever. Hell, Jay had even made up some shit, himself. Mostly, Jay wanted to keep as many people away from Risky’s Pond as he could. He wanted to keep that place to himself. So he had a reason to tell people to stay away from there. But the reporter lady had just looked annoyed and taken off. But Jay hadn’t felt bad. Bottom line was that most of the other kids in town could be really stupid sometimes, and they tended to wreck shit that wasn’t theirs. But not Jay. Jay knew better. He knew not to fuck with other people’s stuff, and he liked to think he was a little bit smart no matter how damaged he was. He knew that CJ was way — way — smarter than he was, but he didn’t really think that he’d ever say that out loud to her. CJ always seemed like if you complimented her the wrong way, she’d get mad, anyway. But he wanted to think that was still pretty smart, himself. And smart kids don’t like to be around stupid kids, most of the time. He knew that. It was why he didn’t have as many friends as some people. Because he was only a little smart. Still, Jay was glad the other kids stayed away from Fell-Munch Road and the woods. Because knowing your way around — that was something where you had to be smart and tough. If you were a pussy, you didn’t belong in this place. Well, except for CJ, who couldn’t help it.

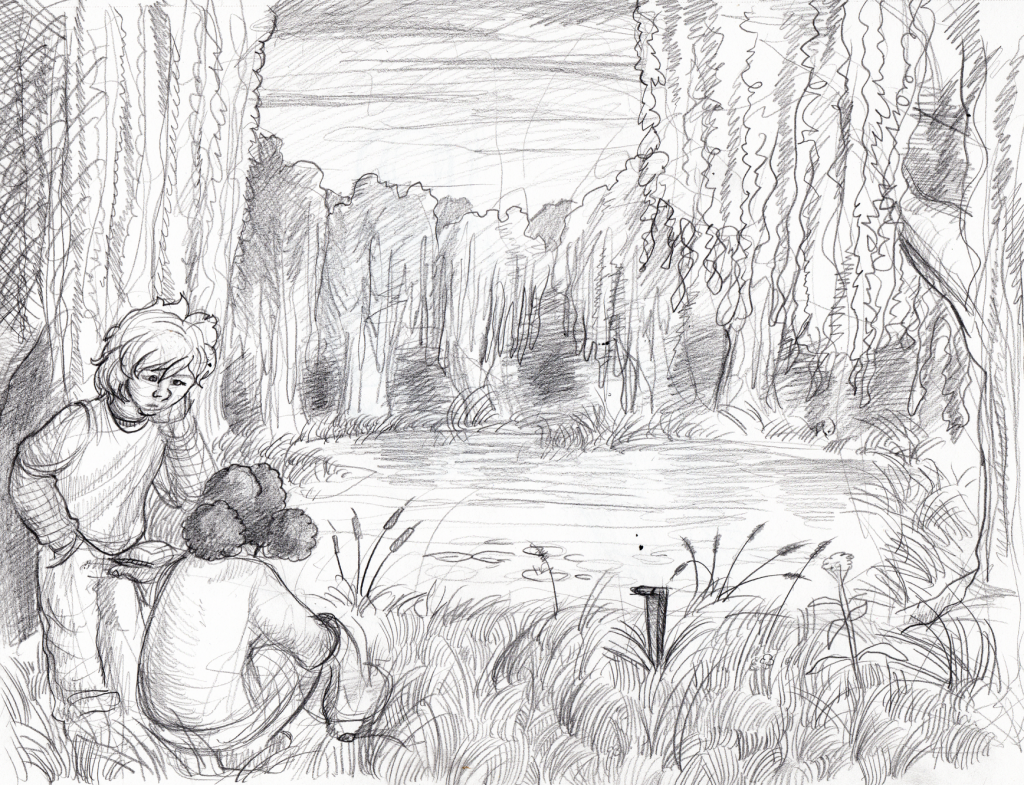

The two of them reached the end of the trail, and walked up to the edge of the pond that gave Risky’s Pond its name. Across the pond were the muddy marshes where the really tall willows grew. The water of the pond, though, looked clean — for a pond — and there were lily pads and loads of cattails all over the edges of the water. “The cattails always made Risky go nuts. Remember how he’d dance around?” Jay asked CJ.

“Yeah,” CJ answered, sounding sincere even with that one word.

Jay sniffled, and he started to think of the first time they’d both met Risky. It was April 6th, 2008. It was at Jay’s seventh birthday party. CJ had been the only guest who wasn’t part of Jay’s immediate family to show up. Back then, Jay had always wanted a pet, was the thing. A dog. Jay’s dad had kept telling him how having a dog was a big responsibility. Jay’s mom had kept telling him that a dog loves you more than anything else in the world. Jay understood that stuff already, even when he was that young. But, the thing was, every time his parents would say that, Jay would get this bad feeling in his stomach. And not the kind when he was feeling really sick. Still, Jay’s family had all gone down to the Dodge Pound few times; that was like a dog rescue place where this guy — Old Man Dodge — ran it to help out dogs who needed help so they could get to be with families. Jay liked the idea, but Old Man Dodge was this crazy old fucker who looked kind of like a mountain man. Old Man Dodge sure knew a lot about dogs, though. But, every time his parents would be there, Old Man Dodge would talk about all that love and responsibility stuff even more than Jay’s parents. And it scared Jay — so much that Jay would always, eventually, not wanna meet the dogs. Jay would act scared. Bu he hadn’t been frightened; it was something else. When it came down to it, having a dog had felt to Jay like something for people who weren’t like him. Jay didn’t feel like having a dog was something he exactly deserved. That he’d just fuck it up somehow. And, besides that, Jay knew he was fucked-up-looking, too. He knew dogs could understand people’s faces. He wouldn’t want to make a dog have to be his dog, because that would be wrong to do to another person, and Jay felt like dogs were just as good as people. When he would go to bed, he would imagine a dog like the one he wanted. He’d imagine the dog coming out of a dark cage, and then the dog would make a yelp sound from seeing Jay and go back in and hide. Because Jay was ugly. And, let’s face it, even little seven-year-old Jay had known that Jay Redwing wasn’t the greatest person to be forced to be around, anyway. Those were just facts, even now. Jay was sick a lot of the time, but it had been worse when he was seven. A lot worse. That had been a bad year. And dogs like to play and go out on walks. Jay was doing better lately, as long as he remembered to take his pills. and stuff. But back then, back when he was seven, things had been different. Jay’s memories of that year were mostly of hospitals and his parents angry or crying. And of his birthday party. Even seven-year-old Jay knew that a dog wouldn’t want to be around all that even some of the time, much less all of thew time. Dogs want to go on walks and play and do stuff an d go swimming and hunting. And it’s not like seven-year-old Jay had been a person with much to offer; no dog would’ve wanted to be around someone like seven-year-old Jay, let alone do anything like lick Jay’s ugly-ass face. No dog would want to go out on walks with him, even if Jay could’ve gone on walks back then. Seven-year-old Jay had always pictured a dog being lonely and sad — and frightened of Jay. The worst would’ve been if Jay had gotten a dog that had turned out to be afraid of him. It wouldn’t be fair to do that to any dog, to make a dog live with Jay Redwing. But at Jay’s seventh birthday party, his mom and dad had gotten him this big brown pit bull who was three years old. The dog didn’t even have a name yet, according to his parents. Later, Jay realized that for Old Man Dodge to have trained him at the Dodge Pound, the dog would’ve had to have a name. But his parents lied about a lot of stuff to make him feel better. Jay’s parents just told him that this dog who didn’t have a name was already house-trained by Old Man Dodge, and had belonged to someone else who’d had to give him up. They never said who. Jay had always wondered about who could’ve given up that dog. And Jay remembered thinking that it was just like his parents to take on used dogs the way they took in used cars for resale. But Jay hadn’t really cared. It hadn’t mattered, because of how Jay had looked into the dog’s eyes and the dog had looked back. And Jay had liked how the dog had looked back so much– and how the dog had run over to lick his face when his parents had brought him into the back yard of the house. The dog hadn’t cared what Jay looked like. He’d raced around the yard, doing his dance like he often did in tall grass and flowers. And when that happens, you don’t hesitate. When you’re a Jay Redwing, and someone is willing to be around you, you just don’t hesitate. Because there are people in this world who don’t get to have chances to have a lot of friends or pets or people who are willing to let them be around. So you don’t hesitate. And oh, man, how that dog had danced all happy and kept jumping into Jay’s arms over and over for Jay to hug him. His mom had said the dog was really ‘frisky’ and his dad had suggested calling him ‘Rusty’ because of the dog’s colors. But Jay hadn’t liked either of those names, and had decided to combine them into ‘Risky.’ Jay’s parents had hated the name, but he’d pointed out to them both that you get names like that when you let your seven-year-old do the choosing. So, Risky it had been, and that had led in turn to the naming of Risky’s Pond, where that same dog had danced through the fields of cattails, acting like every one was an enemy trying to tickle him, kicking up his legs as he bit and barked at the tall plants. “Bet the cattails don’t miss him,” Jay told CJ. His voice cracked, but he quickly cleared his throat.

CJ unzipped her backpack and withdrew another of the Cowboy Cakes, silently offering it to Jay. It had peanut-butter filling.

Jay waved a hand as if to suggest he wasn’t hungry, shaking his head. Then, he moved toward the trunk of the black cherry tree that was closest to the water. He looked at the ground about six feet from the tree, roughly equidistant between the base of its trunk and the edge of the pond. There was a big metal railroad spike sticking out of the ground there. Jay sat down near the spike. “Hey, Risky,” Jay said.

CJ sat down near to him, but still said nothing. She just watched him.

Jay was picturing Risky peeing on the trunk of that nearest tree. Risky had been obsessed with marking every inch of territory possible around the pond. Jay imagined that his dog had been hard at working pissing off the local coyotes. CJ once suggested that the main reason Risky liked to go to the pond so much was specifically because it was the local coyote headquarters at night, and the two of them had woven up a story where Risky and the local coyotes had been at war with each other for the right to control Risky’s Pond. The fact that Jay and CJ had named it Risky’s Pond had been part of that story — they’d wanted to make their loyalties known and had even carved ‘Risky’s Pond’ into the tree just beyond the nearest one, just to show the coyotes who owned this place. Jay had told CJ that, one day, Risky would end up running into the coyotes at the pond, and there’d be this epic fight and Risky would win. Jay had described to CJ the image of what would happen next: Risky as the king of the coyotes, bossing them around and telling them what to do and assigning them top-secret missions to spy on the human world and bring food to him, like fish. Risky loved fish. Jay had often found himself picturing a royal procession where all the local coyotes honored his dog, doing dog bows and dog curtseys. Risky had been seriously bad-ass, as far as Jay was concerned — the dog had grown in a very short time from when Jay got him into a big, powerful pit bull terrier with a booming bark. But Risky wasn’t physically violent or aggressive. He was a dog of bluster, Jay’s dad had said, the kind of dog that liked to make a lot of noise and run around and kick up a lot of dirt, but who didn’t bite people or other animals.

Risky hadn’t liked to fight.

Which is why Risky had barked so loud when those raccoons had shown up at Risky’s Pond. Jay had been ten years old. Risky had been six. CJ hadn’t come along, so the two of them were there alone, with Jay pretending that the two of them were the last hope of a collapsed civilization, trying to find an ancient city of lost technology. That had been a favorite game of Jay’s in his earliest childhood, and had continued to be fun even after he’d made friends with CJ. Before CJ and Risky, though, it had also been a good way to keep himself from thinking too much about why he was always playing alone. On that particular day, the game had been that Jay and Risky were trying to reach a missing caravan of supplies. He’d left his backpack next to the tree marked ‘Risky’s Pond.’ It was full of Jay’s favorite kind of cookie — the ones that looked like kind of like wheels made out of shortbread, but with cherry jam in the centers. Jay remembered Risky had been barking and growling a lot, and Jay had scolded him. “We gotta stick to the mission,” he’d told him. “We gotta find the supplies.” Risky had been irritated. And Jay had realized later on that he’d probably smelled the raccoons.

“Jay?” CJ called, silently.

“Yeah.” Jay said. “I’m okay. I’m just thinking about him.” But Jay wasn’t just thinking about Risky, at that moment. He was picturing the fight. The way Risky had leapt at the raccoons, which wasn’t like him. Maybe he’d smelled that something was wrong. Or maybe it had seemed weird to what Jay could only call his ‘dog senses’ that they weren’t backing off. They were drooling and scary-looking to Jay. They’d seemed big. They’d seemed wrong, somehow. Jay had backed away. Risky had gone after them. Jay had laughed nervously, thinking how his dog must’ve been feeling super-protective of those cookies. He’d yelled “Kick their asses!” to his dog. But even though Risky was big and blustery, he wasn’t a match for a bunch of raccoons. The rodents had kept acting like they were working together against the pitbull. They crawled up on him and beat him up from different angles at once. They went after Risky’s eyes most of all, but they also kept going after his stomach and tail, and all the other soft parts. Every time Risky would roll over from being attacked, or to kick one raccoon off of him, another was scraping at his chest. Jay had heard a cracking sound that had seemed to come from Risky at one point. Risky had whined super loud at that. The big brown dog started coughing, but kept on fighting. And Jay had been too scared to help. And Jay had just stood there through it all. He’d been ten, yeah, but he still felt like he should’ve done something. He’d wanted to run over and start pushing the raccoons off Risky. But he hadn’t done that. He hadn’t taken any action at all. He’d just stood there, letting everything happen. And Jay had watched as the raccoons had kept biting Risky, and Jay had watched as Risky had kept trying to get get back up but kept falling back down and whining. And Jay had watched as Risky had kind of flopped around until the dog had landed face-first in the pond, his back legs on dry land, kind of hanging over the side. And Jay had watched Risky had stopped moving and the pond water turned red. And Jay had watched as the raccoons, none of whom had died or really been hurt all that bad, had dragged his backpack full of cookies away into the woods. Of course, Jay had rushed to Risky’s side after the raccoons had left, but it hadn’t mattered. Risky was dead, his chest opened up all over the place. Jay had remembered seeing Risky’s insides hanging out into the water, and Risky’s one remaining eye had been open, but the dog hadn’t been breathing. Jay had sat there for a really long time. He’d been just a kid back then, and there had been a part of him that had really wanted to imagine that Risky would wake back up. But it didn’t happen. And, with excruciating slowness, ten-year-old Jay had realized that Risky wasn’t going to wake back up. And then he’d stood up and walked silently all the way back into town — the entire one-hour walk. He hadn’t said a word to anyone on the way. He’d gone right to Rick’s grandma’s store — the pawn shop — to talk to Rick. Later, Jay had told Rick he hadn’t remembered much after he’d gotten back to town. To this day, all Jay remembered about their conversation was that he’d told Rick what had happened to Risky. Rick later told Jay that he thought Jay was cool because of ‘you weren’t crying or being a bitch or anything,’ and that ‘you seemed really cool and relaxed, like a man with a plan.’ Rick had also later explained to Jay how Jay had just very calmly walked into the pawn shop to ask Rick if he could borrow ‘some stuff’ — specifically a shovel, one of the souvenir railroad spikes from the old railroad, a top-power air rifle and bunch of ammo. Rick had understood, and had accommodated his friend. Rick hadn’t even told his grandmother about the lended items, on Jay’s promise he’d return the gun and the shovel and pay for the spike and the ammunition later. And that Jay had then quickly left.

Jay’s memories picked up after that — after he’d walked the entire distance back to Risky’s Pond, and buried his dog. And how, After that, Jay had begun to hunt raccoons.

He’d only found two that first day, and he’d killed both of them and thrown their dead bodies into the pond. That had seemed like the right thing to do. He’d kept hunting after that, until he’d exhausted himself and fallen asleep with the air rifle against his chest at the base of the tree nearest the pond. He’d told Risky — even though he knew Risky wasn’t really there — to guard him while he slept. That had seemed like the right thing to do, too. Then, after he’d woken up again, he’d gone home. He’d told the story to his parents, so — of course — he’d been rushed immediately after that to the Sacred Union Hospital. Two weeks and four burning shots of rabies vaccine later, Jay had been back on the hunt again. His father had paid for the air rifle and smoothed things over with Rick’s grandma, who had not been happy about Rick making the call to let Jay borrow things from the pawn shop. But Jay’s dad had taken the shovel and Jay had been allowed to keep the rifle, to his mother’s considerable frustration. And Jay’s hunting had proved successful in the time since that day, because — if you included the five he’d just taken down for Mickey — Jay had killed 27 of the rodents in the three years since the day he’d lost Risky. Jay had been frustrated when Mickey had told him to stop hunting the raccoons for a while. But Mickey was the kind of guy you listened to. And it had felt good to take out five so close together when Mickey had finally asked for the bodies for the prank. It felt good and it felt right — Like some sort of justice, at least. Of course, Jay knew that he’d never be able to be sure that he’d get the ones that had taken down his dog — but every single raccoon that he killed was, potentially, the murderer he was looking for. And Jay was adamant about bringing Risky’s killer to the proper kind of justice. And he was glad to have shared his plans with Mickey. And even more glad that Mickey had trusted him to be part of the prank. To bring five dead raccoons to him. Specifically five. That had been some hard work, but it had been worth it. And Jay had felt good about the prank. Until now, when things were starting to get all weird. To have connected Mickey’s prank to his mission to avenge Risky was starting to seem wrong now. Like Risky wouldn’t be happy to know he’d done that.

“Jay?” CJ called again.

“Yeah,” Jay said, exhaling slowly through his open mouth. Then, “You miss my dog, huh?”

“I do.” CJ got up and walked over to kneel next to where Jay was sitting. “He was a really great guy.”

“He was awesome,” Jay added, looking over toward Jay, tears streaming down his cheeks now. And, in that moment, he didn’t care if CJ saw tears. But he kept as much of his cool as he could. He wasn’t about to make sobbing noises or anything — not in front of even her.

“Raccoons in the wild don’t usually live for too long, Jay,” CJ pointed out, as she often did. “I looked it up, remember? They usually live three or four years, at most.”

“So I’m getting close. I’ll do it for maybe three more years, just to be sure.”

“They’re probably already dead by now,” CJ suggested.

“Some of ’em might’a had babies,” countered Jay.

“Look, Jay — you should-” CJ began. She looked like she was about to say something; it was probably going to be about baby raccoons, some science fact or something, Jay mused with a groan that only echoed in his head — but then she stopped talking as the two of them heard a loud cracking sound from across the pond. It sounded like something big and heavy crashing down on dry branches. CJ was the first to look over toward the sound, her expression going quizzical.

Jay looked toward the other side of the pond just a brief moment later.

There was a boy — he looked even smaller than Jay. The boy was running back and forth through the tall willow trees — and moving fast, given the muddiness of the ground around him. It looked as if the kid was in a real big hurry, or was pretending he was being chased, or something like that — because there was nobody else around, but the kid kept stopping and looking over his shoulder and then running again. More interesting to Jay than what the kid was doing was how the kid was dressed — in an outfit that seemed really strange, even when viewed froƒm where Jay was sitting. The pond was wide enough that Jay couldn’t be sure about everything he thought he was seeƒing, but it looked like the kid had on a big black fur coat, even though it was summer. He had weird black-and-grey gloves on. Jay could also see that there was a black leather belt with a knife cinching up the kid’s jeans. And the kid was wearing a weird mask that looked like it was made of paper mache or something. And the mask looked like it was painted with the colors and patterns of a raccoon’s face.

Be First to Comment